New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

New York City has some of the most ambitious climate goals in the United States and precious little available land on which to build green infrastructure to achieve those goals. So little that the city will need to rely mostly on renewables from distant sources–wind power from Long Island, solar power from upstate, hydroelectric power from Quebec–to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 80 percent by 2050 and derive 70 percent of all its electricity from renewables by 2030.

There is, however, one site right in the center of the five boroughs that is ideally suited–and indeed has been earmarked–for large-scale solar power, battery storage, and waste processing: Rikers Island. In 2021 the City Council and Mayor Bill de Blasio enacted three laws collectively known as “Renewable Rikers” that intend to transform the island into a hub for green infrastructure after the infamous Rikers Island prison complex closes in 2027.

Renewable Rikers directs the Department of Corrections (DOC) to gradually transfer to the Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) “every portion of Rikers Island that the mayor determines is not in active use for the housing of incarcerated persons, or in active use for the providing of direct services to such persons” every six months. At the same time, it directs the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice to study the feasibility of placing composting and wastewater treatment plants and renewable energy and battery storage on the island.

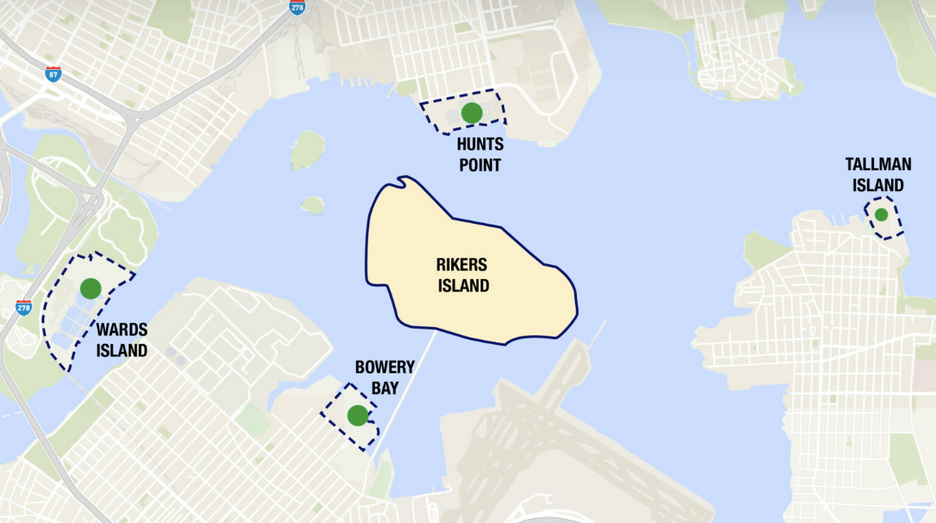

In a potential model for restorative justice, this would also enable the city to remove or consolidate polluting energy and waste facilities from communities which surround the Inner Long Island Sound in Harlem, The Bronx, and Queens, all communities that have suffered environmental and criminal injustice for generations.

“Siting waste facilities on Rikers Island converts its physical characteristics and remoteness from challenges into strengths,” according to a 2016 report from the Lippman Commission, the first city study to assess the feasibility of alternative uses for Rikers Island. One look at a map of the Inner Sound area demonstrates the spatial elegance of the idea.

The timeline for Renewable Rikers would see green infrastructure rising on the island just in time to help New York City hit some of its 2030 benchmarks on the way to larger 2050 targets. The plan, however, is largely dependent on a cooperative mayor. As a result, it’s now playing out against a background of angst and uncertainty as Mayor Eric Adams is calling for a “Plan B,” an ambiguous alternative to closing the Rikers prison by 2027.

Mayor Adams has largely neglected to carry out the land transfers from DOC to DCAS, failed to appoint commissioners to a legally-mandated Renewable Rikers advisory committee, and presided over growing incarceration rates. The jail population on Rikers must be virtually cut in half to close the facility and transfer inmates to new borough-based jails currently under construction. All of this jeopardizes the Renewable Rikers vision and threatens to postpone key components of New York’s clean energy transition along with it.

“There is no option for Plan B. There is no extended timeline in our perspective,” says Shravanthi Kanekal, a Resiliency Planner with NYC Environmental Justice Alliance (EJA). “At the end of the day, it’s in the law. It’s totally unfair to be thinking about Plan B because we have a Plan A that is not currently being efficiently executed.”

EJA is a member of the Renewable Rikers coalition, which championed the legislation and builds on the work of the Close Rikers campaign. The coalition’s first priority is closing the jail and ending the suffering of those incarcerated there, most of whom are still awaiting trial. Conditions have deteriorated so much that the federal government may soon take control of the city’s jails through a process called receivership.

It is unclear how receivership would impact Renewable Rikers, but any delay in closure would impact the already ambitious timeline for the city’s energy transition. It’s also unclear how the city would completely pull off that transition without leveraging for critical infrastructure the 400 open acres smack in the middle of the city.

“Aside from maybe a few landfill sites, we just don’t have that kind of land especially for large-scale solar installation, new substations that connect offshore wind directly into the city, and even large-scale compost processing,” says Dan Zarrilli, who helped shepherd Renewable Rikers forward while serving nearly eight years with the de Blasio Administration including as Director of the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency. “It’s really hard to cite renewable energy in New York City. By at least having some of that on Rikers you have directly connected renewable energy into Zone J and you don’t have to overcome a transmission hurdle to do it.” The New York Independent System Operator divided the state in 11 “load zones” and the New York City area sits within Zone J.

For practical purposes, the state has two energy grids: one upstate where renewable energy is becoming abundant, and another downstate which relies almost entirely on fossil fuels. The transmission projects under construction should bring enough clean power to New York City to achieve the state’s 2030 climate goals, but not the 100 percent clean energy targets beyond that. The state can build more transition, but this comes with its own citing and cost challenges.

Meanwhile, the Adams administration is taking New York’s composting program citywide as part of the city’s bold commitment to send zero waste to landfills by 2030, but the capacity to process that waste is not yet in place. The Lippman Commission estimates that a modern composting facility on Rikers Island could process up to 1,000 tons of organic waste per day, equivalent to the total expected load from Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens, while an energy-from-waste facility there could process as much as 2,000 tons per day of otherwise non-disposable waste.

With regard to battery storage, the city also desperately needs land. According to The New York Times, utilities and private energy developers are engaged in “a rather cutthroat real-estate hustle” as they scramble to build more storage in the five boroughs.

As the CTO and Co-Founder of NineDot Energy, which builds smaller-scale battery storage projects in the city, Adam Cohen is intimately familiar with this. “It’s like a Venn diagram with multiple circles you have to put together: where are these types of projects valuable to the grid, where are they cost-effective to build, where is the zoning appropriate, where are the neighborhood characteristics appropriate–bringing it all together to find the sweet spots is a challenge.” Cohen also points out the advantages of building and storing energy as close as possible to those who will use it. “Distributed energy resources that are close to the end user and close to the load provide lots of tangible benefits…it makes the local power grid more resilient, more reliable, more stable.”

In particular, according to a 2022 report from the New York Power Authority and PEAK Coalition, properly cited and scaled battery storage could allow New York City to close its peaker plants. These plants kick on when energy demand is highest, usually during late afternoons in the summer. They are far dirtier than typical gas plants, emitting twice as much carbon dioxide and 20 times as much nitrogen. Five are clustered around the Inner Sound.

Beyond potential legal or political obstructions, perhaps the most significant challenge for the Renewable Rikers proposal is one which will also only grow as time passes.

“The major challenge will be to secure funding to implement the vision once it’s locked in,” says Eric Goldstein, Senior Attorney and Director of the New York City Environment, People & Communities Program at the National Resources Defense Council, which is also a member of the Renewable Rikers coalition. Redeveloping on the island will be extremely expensive. “The subsurface conditions on the island are notoriously complicated,” says Zarrilli. Deep bedrock, weak soil, and methane deposits resulting from the history of landfill on the island will require construction methods that increase building costs.

“The answer to that is the state’s environmental bond act, the federal infrastructure bills - there is a convergence of significant state and federal funding sources that can be available if the city gets its act together in time.” Funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act is beginning to flow to projects nationwide, especially civil work, but this resource will not last forever.

What can be done to mitigate the delays on Renewable Rikers? “We’re trying to push the administration to consider doing pilot,” says Shravanthi, who points out that DCAS already controls acreage on the island. “We’re pushing for the idea that some of this infrastructure can begin to be installed sooner than 2027… It has been met with some skepticism but we haven’t given up on the idea that that is still possible. We’re still pushing for that to be a possibility.”

Despite the uncertainty, for Shravanthi and other climate and criminal justice advocates, there is no Plan B for New York’s clean energy transition.

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.