Sprawl repair should be pursued using a comprehensive method based on urban design, regulation, and strategies for funding and incentives – the same instruments that made sprawl the prevalent form of development, says Galina Tachieva, director of town planning at Duany Plater-Zyberk and Company.

Sprawl is malfunctioning. It has underperformed for decades, but its collapse has become obvious with the recent mortgage meltdown and economic crisis, and its abundance magnifies the problems of its failure.

Sprawl is malfunctioning. It has underperformed for decades, but its collapse has become obvious with the recent mortgage meltdown and economic crisis, and its abundance magnifies the problems of its failure.

Let us be clear that sprawl and suburbia are not synonymous. There are many first-generation suburbs, most of them built before WWII, that function well, primarily because they are compact, walkable, and have a mix of uses. Sprawl, on the other hand, is characterized by auto-dependence and separation of uses. It is typically found in suburban areas, but it also affects the urban parts of our cities and towns.

Sprawl's defects are not limited to economics. Sprawl is central to our inefficient use of land, energy, and water, and to increased air and water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and the loss of open space and natural habitats. Because it requires a car to reach every destination, it is also to blame for time wasted in traffic, the exponential increase in new infrastructure costs, and health problems such as obesity. Social problems have also been linked to sprawl's isolation and lack of diversity.

Sprawl developments, particularly those in the far-flung exurbs, have recently suffered some of the highest rates of foreclosure. Many homes, and even entire subdivisions, have been abandoned.

Sprawl's future, if current patterns continue, appears no better. Its built form does not serve new and developing markets, providing neither the diversity and stimulation desired by the younger Millennial generation nor the convenience needed by their parents, the Baby Boomers. As Christopher Leinberger has written, many of the car-dependent suburbs on the fringes, unwalkable and poorly served by public transit, "will become magnets for poverty, crime, and social dysfunction."

The party is over.

But we need to house the additional 100 million souls expected to populate this country by 2050.

So what do we do?

The options

The first option is to continue building greenfield sprawl, but that is how we got ourselves into this predicament, and one would hope we have now learned our lesson.

The second option is to abandon existing sprawl. This will not be possible either, as the expanse of sprawl represents a vast investment (of money, of course, but also of infrastructure, time, human energy, and dreams). It also offers opportunities for reuse, and cannot be simply discarded or demolished.

The only valid option is to repair sprawl – to deal with it straight on, by finding ways to reuse and reorganize as much of it as possible into complete, livable, robust communities. Pragmatism calls for the repair of sprawl through redevelopment that creates viable human settlements, places that are walkable, with mixed uses and transportation options. Pragmatism also demands we acknowledge, however, that portions of sprawl may remain in their current state, while others may devolve, reverting to agriculture or nature.

Why sprawl repair is imperative

We need sprawl repair because change will not happen on its own. Sprawl is extremely inflexible in its physical form, and will not naturally mature into walkable environments. Without precise design and policy interventions, sprawl might morph somewhat – a strip shopping center might be scrapped and replaced with a lifestyle center when the next owner comes along – but it is unlikely to produce diverse, sustainable urbanism. It is imperative that we repair sprawl consciously and methodically, through design, policy, and incentives. We need sprawl repair because, in spite of the endless challenges, many opportunities exist. The time is right to deal with sprawl now. Energy costs are rising, meaning long commutes are becoming unaffordable. A changing climate compels us to pollute less. We need to increase physical activity to overcome the epidemic of obesity and chronic diseases. Entire residential and commercial developments are failing. These are the obvious justifications for sprawl repair. But there are other reasons that, while less obvious are equally compelling.

Some of these reasons are economic. For decades, the common wisdom was that exurban residential and commercial development was good for municipalities because of increased property tax revenues. The truth, however, is that municipalities spend much more to expand and maintain suburban infrastructure than they receive in increased revenues. Walkable urbanism, on the other hand, is a much better deal for municipalities. A study in Sarasota, Florida, shows that the county tax yield per acre from an urban mixed-use project is a staggering 3,500 percent more than the tax yield from a suburban mall.

The development industry also has few incentives to continue exurban expansion with lending stalled, property values plummeting, and commuting costs increasing. The market, fortunately, is heading in another direction.

The Baby Boomers and Millenials are creating a major shift in the housing market. Together they represent more than 135 million people, many of them with an orientation toward diverse, compact urbanism.

The population of 21st-century suburbia is very different from the stereotype of 50 years ago that depicted the suburbs as populated by predominantly white, middle-class families with children. The growing presence of ethnic minorities accustomed to driving less and living and working in less space, will contribute to new opportunities for sprawl repair through the engagement of a diverse, multiethnic citizenry.

Sprawl repair also provides the opportunity for economic development. Employment decentralization is a fact, and most businesses are located outside of city limits. Existing single-use, auto-oriented employment and commercial hubs can be redeveloped into complete communities with balanced uses and transportation options. Existing jobs can be saved, and new jobs, many of them green, can be created in the process of – and as a result of – transforming sprawl.

In addition to economic reasons for sprawl repair, the regulatory environment that supports sprawl has already begun to change. Form-based codes have been approved in hundreds of municipalities around the U.S. This shift in the regulatory framework makes smart growth development legal again and assists sprawl repair initiatives.

Regional and statewide planning practices can provide discipline and coordination on a large scale. Many counties, whole regions, and even entire states have already embraced policies that do not foster sprawl, making the repair of sprawling suburbs more feasible, as public resources are channeled to incentivize sustainable growth. In the six-county metropolitan region of Sacramento, California, an association of local governments completed a "Blueprint for the Future." The plan addresses growth through 2050, and encourages compact developments near mass transit, thus saving billions of dollars that would otherwise be needed for freeways, utilities, and other infrastructure. Statewide projects such as Louisiana Speaks endeavor to create coordinated solutions for growth and outline opportunities for infill and repair.

Even at the federal level, agencies have come together to address growth in a holistic, multi-disciplinary manner that should help with sprawl repair. The HUD-DOT-EPA interagency partnership for sustainable communities will coordinate federal housing, transportation, and other infrastructure investments to protect the environment, promote equitable development, and help address the challenges of climate change. This is an opportunity for sprawl repair initiatives to be combined with federal funding, and possibly legislation.

Market forces, policies, and incentives, however, will not be sufficient to achieve the regeneration of our unsustainable suburbs. We also need specific strategies and design techniques.

How to Repair Sprawl

Sprawl has been aggressively promoted and encouraged, and the approach to repair must be the same. It should start soon, because despite the severity of the building industry meltdown, development has not stopped, and it is urgent that such activity be redirected to places that have potential for redevelopment – defunct malls, failing office parks and residential subdivisions, empty parking lots, abandoned golf courses – rather than to building more sprawl.

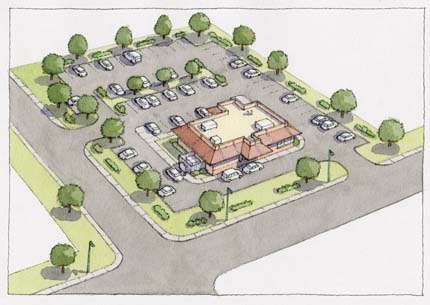

Sprawl repair should be pursued using a comprehensive method based on urban design, regulation, and strategies for funding and incentives – the same instruments that made sprawl the prevalent form of development. Repair should be addressed at all urban scales, from the region down to the community and the building. Strategies should range from identifying potential transportation networks and creating transit-connected urban cores to transforming dead malls into town centers, reconfiguring conventional suburban blocks into walkable fabric, and adapting and expanding of single structures. The sprawl repair method should identify deficiencies in typical elements of sprawl and determine the best remedial techniques for those deficiencies. Rather than the instant and total overhaul of communities, as promoted so destructively in American cities half a century ago, this should be a strategy for incremental and opportunistic improvement.

Sprawl must be fixed. The good news is that we have the tools to do it. Rather than focus on the problems, let's get to work.

Galina Tachieva is a partner and director of town planning at the central office of Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company, in Miami, Florida and the author of the Sprawl Repair Manual. For two decades, she has designed and implemented human-scale, sustainable communities around the world, from downtowns to retrofits.

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.