Most people value walkability, yet most communities underinvest in pedestrian facilities. Some jurisdictions are investing more in sidewalks and crosswalks in order to better serve community values.

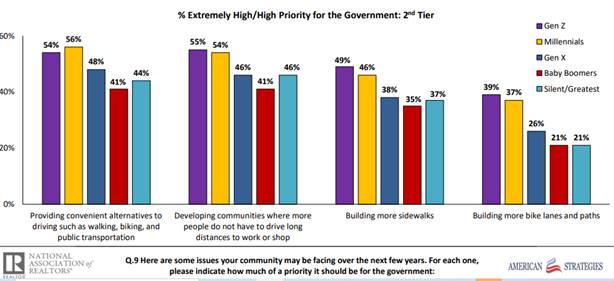

The National Association of Realtors just released its latest Community and Transportation Preference Survey, the fifth in its series. As with previous versions, it found that Americans place a high value on walkability, including complete sidewalk networks, and services—such as shops, cafes and restaurants—within convenient walking distance. They also express strong support for investing in sidewalks, as illustrated below.

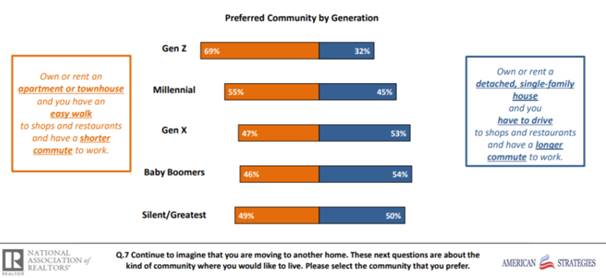

A majority (77 percent) would spend more for a house in a walkable community, and 53 percent would choose an attached house (apartment, condo, townhome) in a walkable neighborhood over a detached single-family home in a less walkable area. This preference for walkability is particularly strong (69 percent) for Gen Z, the youngest age group.

Other data sources find similar results. Real estate market studies find that homes in walkable neighborhoods are worth 5 to 20 percent more than comparable houses in auto-dependent areas. Since U.S. households spend on average about $20,000 annually on housing, this implies that an average household would spend $1,000 to $4,000 more per year for a home in a walkable neighborhood. These preferences are rational: living in a compact, walkable urban neighborhood reduces transportation costs, improves health, provides more independent mobility for non-drivers, and reduces commute duration. The NAR survey found that households living in walkable communities are more satisfied with their quality of life.

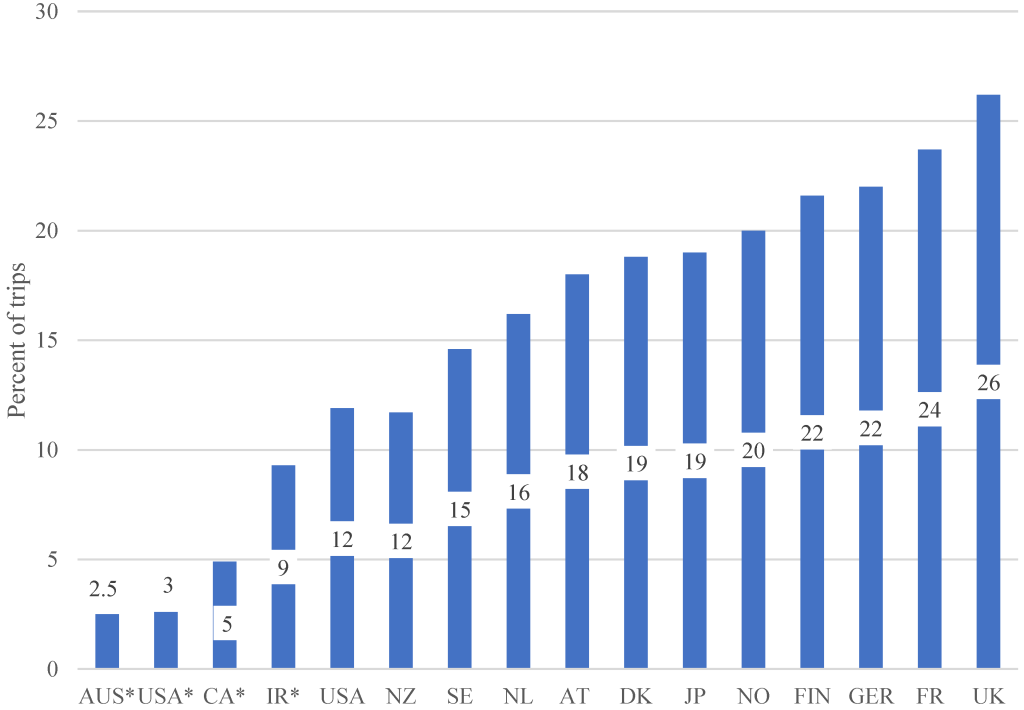

However, current transportation planning fails to respond to these consumer values. Approximately 60 percent of the NAR survey respondents report that they are sometimes forced to drive because they lack alternatives. A recent study by professors Ralph Buehler and John Pucher, “Overview of Walking Rates, Walking Safety, and Government Policies to Encourage More and Safer Walking in Europe and North America,” found that walking mode shares are much lower in North America and Australia than in peer countries, as illustrated below.

These low rates of walking reflect decades of underinvestment in pedestrian facilities. My report, Fair Share Transportation Planning, summarized in a recent Planetizen column, shows that most North American communities spend a far smaller portion of their transportation budgets on pedestrian facilities than walking’s share of trips, traffic deaths and transportation system users. This is unfair and inefficient, since if forces people to drive for trips that would be made by walking if pedestrian facilities were improved.

Walking is the most basic, inclusive, healthy and affordable form of travel. It can also be enjoyable and sociable if conditions are right. A rational transportation planning process prioritizes walking over other modes in planning and funding, reflecting a sustainable transportation hierarchy.

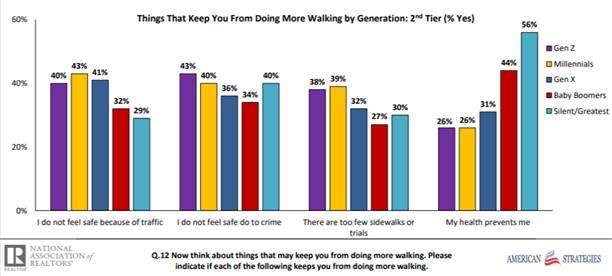

The NAR survey found that inadequate sidewalks are one of the factors that discourage walking, as illustrated in the figure below. Traffic risk is another concern. Completing sidewalk and crosswalk networks provides large safety benefits. The study, Analysis of Factors Contributing to “Walking Along Roadway” Crashes, found that providing walkways separated from travel lanes prevents up to 88% of crashes involving pedestrians walking along roadways, and sidewalks reduce other risks including head-on, sideswipe, and fixed-object crashes. Roadways without sidewalks are more than twice as likely to have pedestrian crashes as locations with sidewalks on both sides of the street. Providing raised medians at crosswalks can reduce pedestrian crashes by 39 percent to 46 percent.

Crime is also a concern; studies find that crime rates tend to decline as pedestrian traffic increases in an area, providing more passive surveillance so improving and encouraging walking can help reduce this problem. Sidewalk and crosswalk improvements can also reduce health constraints by creating conditions where people with disabilities feel comfortable and safe.

A complete pedestrian network is particularly important for people with disabilities and low incomes, and transit users since most transit trips include walking links. Sidewalks and crosswalks also benefit motorists by providing access between parked cars and destinations.

Regulations, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), require that that all transportation facilities meet universal design standards, which means that they are sufficiently smooth and wide, and have ramps that accommodate wheelchairs and rollators. Those features not only benefit people with mobility impairments, they are also important for pedestrians pushing strollers and handcarts, tourists with wheeled luggage and business people with wheeled briefcases. To maintain quality control, transportation agencies can hire and train wheelchair users to be pedestrian facility experts, giving them input in design and final approval of new facilities.

However, such regulations alone cannot create walkable communities: we need sufficient funding to complete pedestrian networks. For example, if a basic sidewalk costs $40 per linear foot and universal design requirements increase this to $60 per linear foot, a city with a million dollar pedestrian budget can build 25,000 feet of basic sidewalk or just 16,666 feet of universal design sidewalk. To create walkable communities and achieve social equity goals the city must increase its pedestrian facility budget so that all streets have ADA-compliant sidewalks, paths and crosswalks that accommodate all users.

Experience indicates that completing pedestrian networks increases walking mode shares and reduces driving, providing large benefits. The U.S. Federal Highway Administration’s Nonmotorized Transportation Pilot Program invested about $100 per capita in pedestrian and cycling improvements in four typical communities (Columbia, Missouri; Marin County, Calif.; Minneapolis area, Minnesota; and Sheboygan County, Wisconsin), which increased their walking trips 23 percent and bicycling trips 48 percent, and reduced driving about 3 percent. Crash rates declined, and the program provided health and environmental benefits. Researchers Guo and Gandavarapu (2010) estimate that completing the sidewalk network in a typical U.S. community would increase walking 15 percent and reduce vehicle travel 3 percent.

A few studies have investigated the costs of completing pedestrian networks and some North American communities are funding programs to accomplish this. For example, a recent study by researchers Alexis Corning-Padilla and Gregory Rowangould, Sustainable and Equitable Financing for Sidewalk Maintenance, used detailed field data to estimate that in Albuquerque, New Mexico, improving all sidewalks to optimum standards would cost approximately $54 million, which sounds expensive, but averages just $60 per capita or $6 annual per capita if implemented in ten years.

The Washington State Department of Transportation’s Active Transportation Plan estimates that upgrading the state transportation system to maximize active travel safety would cost $5.7 billion, which is approximately $750 per capita, or about $75 annual per capita over ten years. This represents about 13 percent of that state’s transportation budget, which is the approximate share of trips made by walking and bicycling.

In Denver, Colorado, an engineering study found that approximately 40 percent of the city’s sidewalks are missing or substandard. Filling these gaps would cost between $273 million and $1.1 billion, averaging $385 to $1,550 per capita, or about $40 to $150 annual per capita over a decade. City residents recently approved Ordinance 307, which will collect special property taxes to do this, demonstrating that citizens support pedestrian improvements, even if they must pay.

The city of Los Angeles has more than 9,000 miles of sidewalks, of which roughly 40 percent are rated inadequate. The city spends millions of dollars annually in sidewalk injury settlements. A 2016 class-action lawsuit by disability rights advocates requires the City to spend $1.4 billion over 30 years to fix them, averaging about $12 annual per capita, although progress is slow. A recent article, “A Faster Path to Safer Sidewalks,” by Professor Donald Shoup recommends requiring property owners to upgrade sidewalks when their homes are sold and they have plenty of money to finance those improvements. Every community should implement that law.

This suggests that completing sidewalk and crosswalk networks typically requires doubling pedestrian facility budgets. That may seem expensive if compared with current pedestrian spending but it is tiny compared with expenditures on other modes. My research indicates that each year communities spend, on average, about $50 per capita on sidewalks and crosswalks, $180 per capita on public transit subsidies, $1,000 per capita on public roads and traffic services, more than $2,000 per capita on government-mandated parking facilities, while motorists spend about $6,000 on their vehicles. Pedestrian investments can repay their costs many times over by reducing motor vehicle expenses. Considering all economic, social and environmental impacts, sidewalk and crosswalk improvements provide terrific economic returns.

This is not just a city issue. Most suburbs are unwalkable and can benefit tremendously from sidewalk and crosswalk improvements, complete streets programs, infill development, and other sprawl repair strategies.

This indicates that pedestrian improvements have broad public support and are cost effective, but current institutions are inadequate for the task. Our transportation planning process favors motor vehicles over active modes; travel surveys often undercount walking trips, transportation agencies collect little information on walking conditions, and pedestrian infrastructure receives much less funding than other modes.

These problems are invisible to most decision-makers, practitioners and citizens. To correct these shortcomings, planners must provide leadership. It is up to us to highlight the significant unmet demand for pedestrian facility improvements, develop better pedestrian data and evaluation tools, and identify funding reforms for more optimal investments in sidewalks, crosswalks and paths.

For More Information

AARP and CNU (2021), Enabling Better Places: A Handbook for Improved Neighborhoods, American Association of Retired Persons.

ARUP (2020), Cities Alive: Towards a Walking World.

Torsha Bhattacharya, Kevin Mills and Tiffany Mulally (2019), Active Transportation Transforms America: The Case for Increased Public Investment in Walking and Biking Connectivity, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy.

Justin Boyar (2016), Walkability: Why it is Important to Your CRE Property Value, JLL Real Estate.

DfT (2020), Gear Change: A Bold Vision for Cycling and Walking, UK Dept. for Transport.

Gehl Architects (2013), Istanbul: An Accessible City – A City for People, EMBARQ Turkey.

ITE (2023), Residential Local Street Sidewalk Survey, Institute of Transportation Engineers.

Knight Frank (2020), Walkability and Mixed-Use: Making Valuable and Healthy Communities, The Princes Foundation.

Becky P.Y. Loo (2021), “Walking Towards a Happy City,” Journal of Transport Geography, Vo. 93.

NACTO (2016), Global Urban Street Design Guide, National Association of City Transportation Officials.

National Walkability Index by the USEPA ranks Census block groups according to their relative walkability, taking into account intersection density, housing and employment diversity, and proximity to public transit services.

Michael A. Rodriguez and Christopher B. Leinberger (2023), Foot Traffic Ahead: Ranking Walkable Urbanism in America’s Largest Metros, Smart Growth America.

Donald Shoup (2010), “Fixing Broken Sidewalks,” Access 36 (www.uctc.net/access); Spring, pp. 30-36.

Erica Simmons, et al. (2015), White Paper: Evaluating the Economic Benefits of Nonmotorized Transportation, FHWA-HEP-15-027, Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center

Street Mobility Project, provides practical tools for measuring community severance (roads that create barriers to walking and cycling) and overcoming barriers to walking by older people.

Walk Friendly Communities is a national program sponsored by the U.S. Department of Transportation to encourage towns and cities to establish a high priority for supporting safer walking environments. The Resources section provides useful information for bicycle and pedestrian planning and analysis.

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.