Shadeways (covered sidewalks) and pedways (enclosed, climate controlled walkways) can provide comfortable walkability in hot climates. The Cool Walkshed Index can help plan these facilities.

Nearly all modern automobiles and transit systems have air conditioning for passenger comfort. My new report, Cool Walkability Planning, investigates why and how communities can deliver similar comfort to pedestrians.

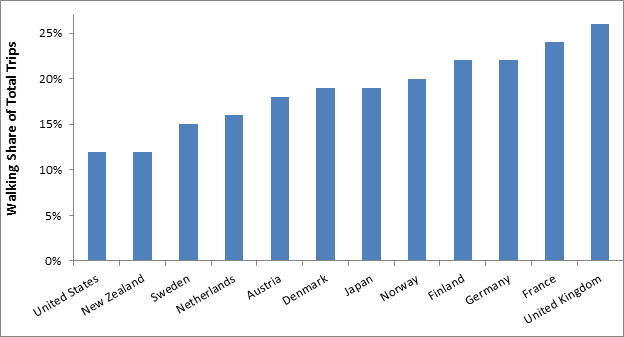

Walking (including variants such as wheelchairs, hand carts, and low-speed scooters) is the most basic mode of transportation; it provides efficient mobility, exercise and enjoyment. Improving walking conditions and increasing walking activity can provide many economic, social and environmental benefits. Among developed countries, 12 percent to 26 percent of total trips are by walking, as illustrated below, with higher rates in denser neighborhoods, in areas with good walking conditions, and among lower-income residents.

Pedestrian mode shares in various countries

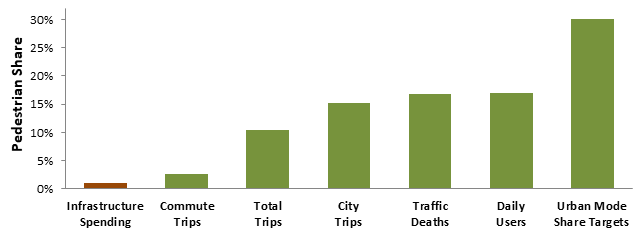

Despite its importance, walking currently receives little support. Most communities spend less than $50 annually per capita on sidewalks, crosswalks and paths, which is less than 1 percent of their total transportation infrastructure investments. This is far smaller than indicators of walking demands, as illustrated below.

Pedestrian share of infrastructure spending compared with indicators of demand

This is unfair and inefficient. It deprives pedestrians of safe and convenient walking conditions, and forces travelers to use more costly and unhealthy modes for trips that, given better infrastructure, would be made by walking.

Of course, the devil is in the details. Walkability planning must reflect each community’s unique demographics and geographic conditions. I was reminded of this recently while working on a sustainable transportation plan for a hot climate city where temperatures often exceed 40 degrees Celsius (105 Fahrenheit) and sometimes 50 Celsius (120 Fahrenheit).

This is an important challenge for planners. How can we create more comfortable walking conditions in overheated cities? Let's investigate this problem.

Hot-climate pedestrian comfort

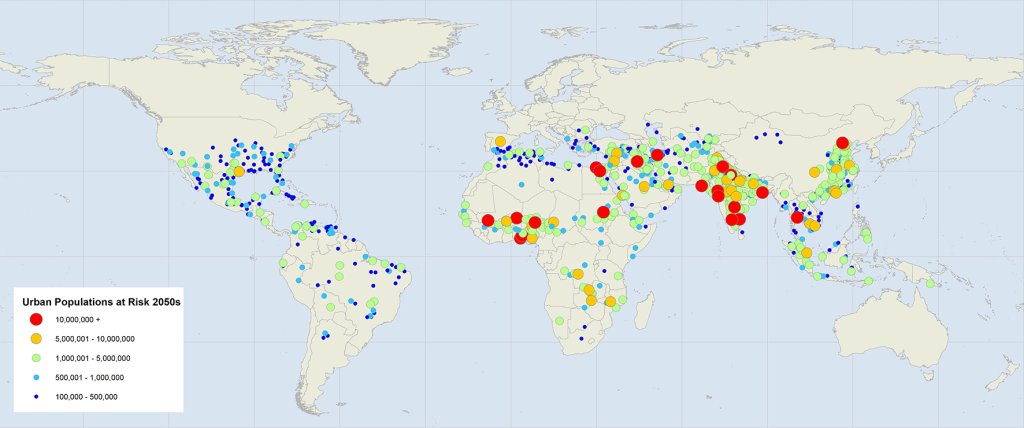

Outdoor physical activity, including walking, is uncomfortable and unhealthy in temperatures over 90°F (32°C) during the day and 75°F (24°C) at night. Many communities already experience extreme heat, and this is likely to increase significantly in the future due to global warming and urbanization, as illustrated below.

Cities predicted to experience extreme heat by 2050

Extreme heat is particularly severe in cities due to the heat island effect, which increases ambient temperatures 1-7°F due to more dark surfaces (pavement and roofing), reduced green space (such as tree cover), and heat-generating activities (fuel and electricity consumption). Pedestrians experience heat discomfort and risks when walking on unshaded sidewalks because they are physically active and absorbing heat from the sun above and radiated from below.

There are many ways to reduce urban heat, as discussed in my previous column, Cool Planning for a Hotter Future. We can design buildings for natural and mechanical cooling, provide more shade, and increase greenspace and tree cover. Pedestrians can be protected with shadeways (shaded sidewalks) and pedways (enclosed, climate-controlled walkways). The Abu Dhabi Urban Street Design Manual and the Abu Dhabi Public Realm Design Manual include detailed shadeway design recommendations. To be effective these must be planned as integrated networks to provide convenient and comfortable pedestrian connections between homes, services and public transit within a walkshed (the area people can comfortably walk).

Below are examples of shadeway designs.

Traditional streets are narrow and shaded (John & Tina Reid)

Trees can provide beautiful shadeways

Structured shadeway in Dubai

Commercial shadeway structure

Shade canopies can incorporate solar panels, such as the 196 meter walkway connecting the Singapore Discovery Centre with a nearby bus stop, illustrated below. These can power pedway cooling systems.

Shadeway with solar panels in Singapore

The Cool Walkshed Index

To facilitate hot climate pedestrian planning I designed the Cool Walkshed Index (CWI) summarized below. This can be used to evaluate pedestrian thermal comfort for a destination or area. For example, CWI rating can be used to evaluate pedestrian access for a particular building or neighborhood; identify where shadeways and pedways are justified; and set targets for pedestrian improvements. CWI maps can show which sidewalks, paths and roads have inferior, adequate or excellent hot-climate walkability. To evaluate economic opportunity planners can measure CWI ratings from homes to services and worksites, and to evaluate transit accessibility planners can measure the CWI ratings to transit stations.

Cool Walkshed Index (CWI) RatingsA: Connected to a continuous, enclosed, climate controlled pedway that provides access to commonly-used services (shops, restaurants, social and cultural activities), and high quality public transit.B: Located within 1,000 feet (300 meters) of a pedway entrance where ambient temperatures frequently exceed 38°Celsius (100° Fahrenheit); and within 300 feet (100 meters) of a pedway entrance where temperatures exceed 40° Celsius (120° Fahrenheit).C: Connected to a continuous shadeway (walkway with at least 80% shade coverage during mid-day) that provides access to commonly-used services and high quality public transit.D: Connected to a continuous but unshaded walkway that provides access to commonly-used services and high quality public transit.E: Connected to an incomplete walkway that provides inadequate access to local services and public transit.F: Has major barriers to walking to local services and public transit. |

Currently, most buildings and neighborhoods have CWI access E (incomplete and largely unshaded sidewalks and paths) or D (complete but largely unshaded sidewalks and paths) to nearby services and activities. Few neighborhoods have well-developed shadeways that provide C ratings, or pedway networks that provide B or A ratings.

CWI ratings can provide useful guidance for individuals making location decisions and communities making infrastructure planning decisions. For example, when shopping for a home in a hot climate city, potential residents should be interested in the quality of their pedestrian connections to nearby services and transit stations. Households can rationally pay more for a home with a higher CWI rating if that significantly improves their walkability comfort and reduces their vehicle and parking costs. Developers and property owners can justify helping finance neighborhood shadeways or paying for a pedway connection in order to raise their CWI ratings.

Of course, shadeways and pedways must be properly designed and managed. They should reflect universal design principles to accommodate all types of users including people with disabilities, families with children, travellers with hand carts and wheeled luggage. They should be designed with sufficient capacity to avoid crowding, and well maintained for comfort, safety and attractiveness.

Examples

Many cities have pedway networks (basement versions are called underground cities, and elevated versions are called skyways), although most are limited in scale, serving only a portion of total destinations and walking trips.

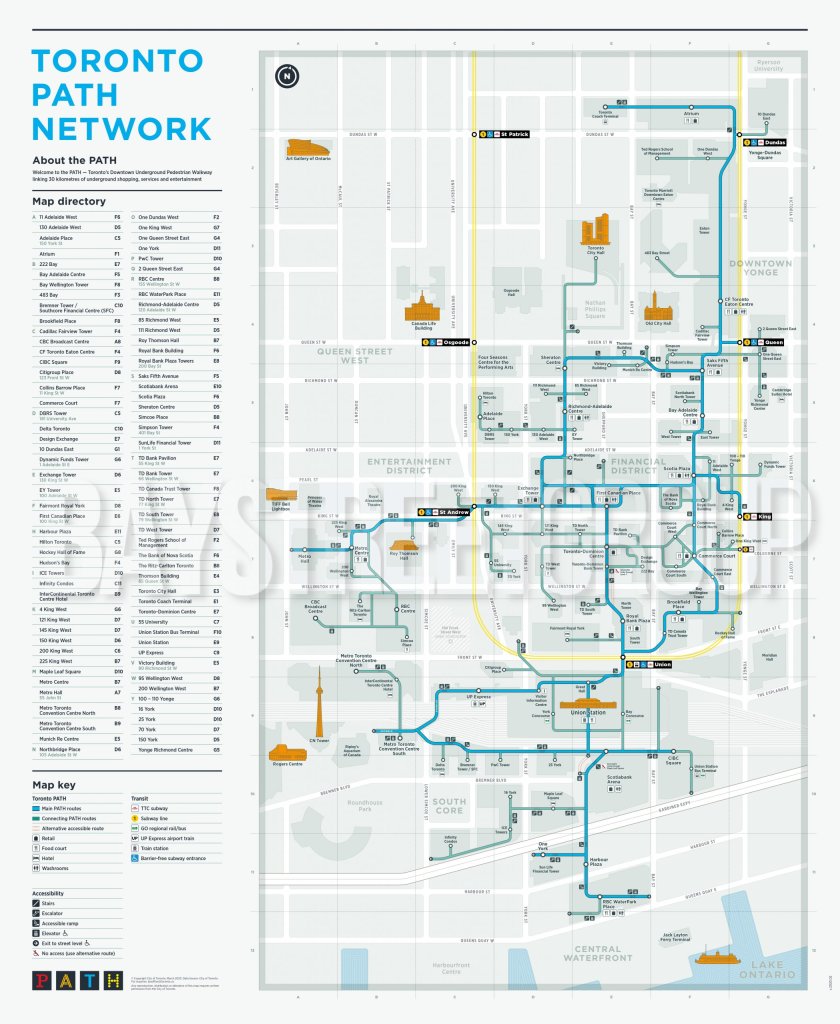

Toronto’s PATH network, illustrated below, is one of the most complete, with more than 30 kilometers of enclosed walkway that connect directly to or close to most downtown buildings, public transit stations, and attractions. Chicago, Edmonton, Montreal are other cold-climate cities with extensive pedways.

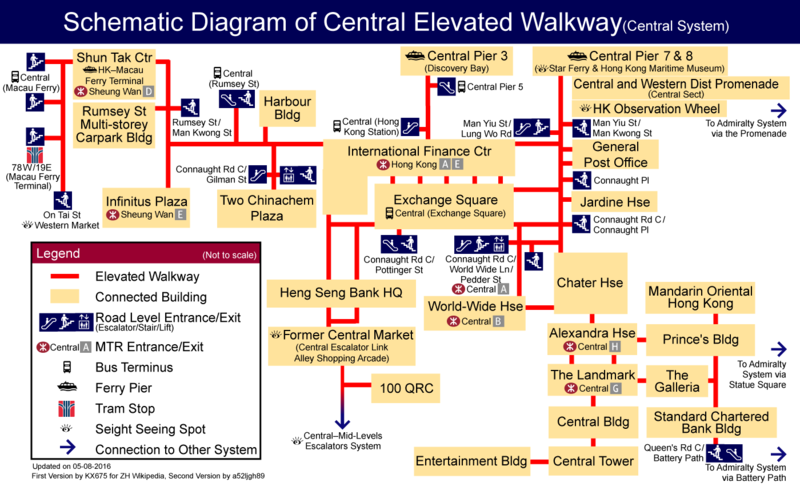

There are also pedway networks in hot climate cities. Hong Kong has two multi-level walking networks, the Central System and the Admiralty System, which connect many buildings, transit stations and attractions.

Hong Kong’s pedway network

Bangkok’s Skyway system is suspended between the elevated Skytrain tracks. It was promoted as a convenient and comfortable alternative to walking on city streets with cracked and crowded sidewalks and crossing busy traffic, but as of 2020 only 15% of the proposed system is completed and progress is slow. Kuala Lumpur’s KLCC - Bukit Bintang Walkway, completed in 2012, is a 1.2 kilometer enclosed and air conditioned pedestrian bridge that connects the Convention Centre, shopping malls, hotels and other major destinations.

Singapore’s J-Walk is a network of approximately 25 kilometers (15 miles) of elevated and underground pedestrian walkways that connect commercial, health-care and institutional developments to public transport stations.

Singapore Western Region Pedway Plan

Seoul, South Korea has a well-developed underground network that connects metro stations to popular attractions such as shopping centers and museums; Myeongdong and Hoehyeon underground streets are the most famous. Taipei, Taiwan has underground pedways connecting metro stations to nearby shopping malls and other attractions.

Many Chinese cities have underground pedway networks. Guangzhou has at least 16 around rail stations. The largest is in Zhujiang New Town which connects metro stations to the basements of over 35 office towers, numerous shopping malls, medical centers, and other downtown attractions. Harbin has several large, multi-level underground shopping areas such as the roundabout intersection of Xida Zhi street and Hongjun street, where three levels of markets following streets from four directions meet under a giant atrium. Hangzhou has an underground mall in Wulin Square connected to a subway station of the same name and nearby office buildings. Nanjing has an underground mall around Xinjiekou metro station. Qingdao has two small underground shopping areas, one at the head of the Zhanqiao pier and one west of the Qingdao guest house.

Dubai’s Metro system has beautiful stations, some with enclosed walkways over busy highways, including the half-mile pedway between the Burj Khalifa Station and the Dubai Mall, illustrated below.

Burj Khalifa Station to Dubai Mall pedway

Potential benefits and costs

Shadeway and pedway benefits and costs are described below. For more information see “Evaluating Active Transport Benefits and Costs,” (Litman 2023a).

Benefits

Improved user comfort and fitness. Pedestrian improvements directly benefit walkers, and by increasing walking activity improve public fitness and health.

User cost savings. Residents of walkable urban villages typically own about half as many vehicles, drive about half as much, and spend about half as much on transportation as in automobile-dependent areas.

Higher property values. Residential and commercial property values tend to increase with improved walkability and access to high quality public transit services. One study found that 10-point increase in Walk Score is associated with a 5% to 8% increase in commercial values with even larger gains from proximity to high quality public transit stations.

Increased local business activity and tax revenue. Businesses located in walkable commercial districts tend to have more customers and sales. One major study found that improving walkability increases local retail sales by 80%.

Reduced traffic problems. Residents of walkable urban villages typically make about half as many vehicle trips as in conventional, automobile-oriented areas, which reduces road and parking facility costs, traffic congestion, crash risk and pollution emissions.

These benefits tend to increase with scale. A single walkway that link a few buildings will have modest travel impacts and benefits, but as more buildings connect the number of potential users and services expands, increasing the value to businesses, consumers and travellers. Extensive pedway networks in cities like Toronto link hundreds of businesses with tens of thousands of daily customers, or you could say, link many thousands of people with hundreds of businesses and activities, resulting in more efficient economic activity with less traffic and associated costs.

These benefits tend to increase with Smart Growth policies that create compact and mixed urban villages where most commonly-used services and activities, including high quality public transit, are located within a fifteen minute walk of most homes and worksites. To maximize their cost efficiency shadeways and pedways require a village with at least 10,000 residents or workers, or about 15 residents or workers per acre, similar to what is required for high quality public transit.

These benefits also tend to increase with the implementation of TDM incentives, such as reduced parking mandates, more efficient parking pricing (motorists pay directly for using parking facilities), public transit service improvements, commute trip reduction programs, and traffic prioritization, so travellers have more reasons to shift from driving to walking and public transit.

Costs

Shadeways and pedways are relatively costly compared with basic sidewalks and paths. A typical sidewalk costs $50 to $150 per linear foot, depending on materials and conditions. Adding a sturdy canopy can double those costs, and enclosed air conditioned pedways are even more expensive, particularly for underground tunneling or major overhead structures, , which require escalators and elevators to provide universal access, so they cost many thousands of dollars per foot. However, they are inexpensive compared with the full costs of motor vehicle travel.

Because they are expensive, pedways are mainly justified in dense downtowns where they can connect many high-rise buildings. It would be very expensive to connect all buildings, including smaller buildings (CWI A); a more realistic goal to locate most buildings within a short walk of pedway entrances, such as 300 feet (100 meters) for over 38°C (100° F) and up to 1,000 feet (300 meters) for over 40° C (120° F).

Urbanists sometimes criticize pedways for being sterile, privatized spaces that remove pedestrians from the public realm, reducing access to smaller shops and street activity, and excluding lower-income people. They are also criticized for their air conditioning energy consumption.

These criticisms might be legitimate to the degree that travellers choose between walking in pedways or vibrant public sidewalks, but not if travellers choose between walking in pedways and driving. Well-designed pedways networks not only reduce automobile traffic and associated costs, they can also make city center living more attractive and successful, reducing sprawl and sprawl-related costs.

Pedways can be planned to maximize the quality of the walking experience and encourage community cohesion. They should be interesting and attractive places that provide opportunities for spontaneous social interactions. Pedways can include places to sit, viewpoints, artwork, and non-commercial community spaces including museums, galleries, libraries and indoor playgrounds. Portions of pedways can be planned and managed as extensions of public transit stations. Toronto’s PATH pedway network includes many family activities. Similarly, visitors often tour Chicago’s underground pedway attractions.

Air conditioning has economic and environmental costs, so it is important that buildings and pedway networks rely on passive cooling where possible, and maximize cooling system efficiency. However, passive cooling can be inadequate in extreme heat, so some air conditioning may be needed. With modern high performance solar panels and air conditioning systems, shadeway solar arrays should be able to power most or all pedway cooling loads. Pedway energy costs are likely to be much less than what is required if residents drive rather than walk.

Business case example

As previously described, most jurisdictions currently spend about $50 annually per capita to build and maintain public sidewalks and paths (Litman 2023b). A few jurisdictions, such as Albuquerque, Denver, Los Angeles, and Washington State spend about twice that to complete their sidewalk networks and meet universal design standards. Building shadeways on main sidewalks (those on arterials, around shopping districts, and to school) would probably require an additional $50 annually per capita.

Assume that pedways cost on average $10 million per mile to build, which is comparable to the cost of adding an urban arterial lane in a large U.S. city. Of course, this will vary depending on conditions, with lower costs for pedways developed in conjunction with building and roadway projects, and higher costs when they are retrofitted or where conditions are particularly challenging.

Assume that in a typical transit-oriented village, a basic pedway network that provides CWI B (most homes and businesses are located within a 300 to 1,000 feet walk of a climate-controlled pedway) requires two pedway miles, and a more complete pedway network that provides CWI rating A to most homes and worksites (they connect directly to a climate-controlled pedway that accesses commonly-used services and a major transit station) requires four pedway miles.

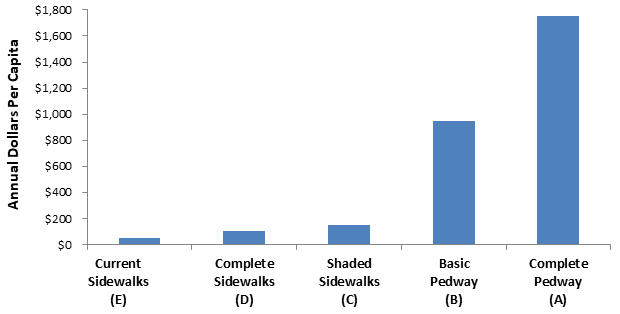

The figure below illustrates the per capita costs of achieving various CWI ratings. CWI E (the incomplete sidewalk networks that currently exist in most communities) cost about $50 annually per capita. CWI D (a complete sidewalk network) costs about $100 annual per capita. CWI C (sidewalks with shades on busy routes) would probably cost about $150 annual per capita. Achieving CWI B (a basic pedway network that provides enclosed walkways close to most homes and worksites) would cost an estimated $950 annually per capita, and CWI A (pedways that connect to most residences and worksites) would cost $1,750 annual per capita if the costs are distributed among 25,000 urban village residents and workers.

Estimated costs of achieving Cool Walkshed ratings

Are these facilities expensive? To develop comprehensive shadeway and pedway networks communities will need to increase their pedestrian expenditures several fold, which makes them seem expensive. However, compared with what governments currently spend on roads and traffic services (about $1,000 annually per capita), what businesses spend on parking facilities (more than $2,000 annually per capita), and what motorists currently spend on vehicles in automobile-dependent areas (more than $6,000 annual per vehicle), pedways are inexpensive. If shadeway and pedway investments allow road, parking and vehicle costs to decline 5% to 20% they will more than repay costs investments and provide other economic, social and environmental benefits. They become more cost effective if developed in conjunction with building and roadway construction (which minimizes their costs); if implemented in dense urban villages (which maximizes their usefulness); and if implemented with TDM incentives (which increases their use).

Conclusions

Improving walkability (including variants such as wheelchairs, hand carts, low-speed scooters) can provide significant benefits to people, businesses and communities, particularly in dense urban areas where land values are high and vehicle travel is costly. However, walking can be uncomfortable and unhealthy in hot climate cities, particularly those that often experience extreme temperatures (over 40° Celsius, 105° Fahrenheit). These conditions make walking unattractive and infeasible during many days.

We have solutions! A well-planned networks of shadeways (shaded sidewalks) and pedways (enclosed, climate-controlled walkways) incorporated into a compact urban village can provide convenient, comfortable and efficient non-auto access during extreme heat. They can create multimodal communities where residents, workers and visitors rely more on walking and public transit, reduce vehicle use, save on vehicle costs, and require less expensive road and parking infrastructure. This provides large direct and indirect benefits. Many cities have some shadeways and walkable, air conditioned shopping centers, but few have comprehensive shadeway and pedway networks that make walking comfortable between most homes, worksites, services and transit during hot days.

To be successful these networks require public support. Their development requires effective planning and business models. They experience economics of scale – they become more effective and cost-effective are they expand and connect more people (potential customers and employees), businesses, and services, so property owners should be encouraged or required to connect and support to them. Pedways are far more costly than basic sidewalks so creating these networks will require significant increases in pedestrian facility investments. However, these costs are far lower than what governments spend on urban roadways, businesses spend on parking facilities, and motorists spend on vehicles in automobile-dependent areas. Although pedway air conditioning consumes energy, this is far less than what travellers would otherwise use if they drive, and can be offset if shadeways have solar panels. Shadeway and pedway costs can be minimized if they are integrated into building and urban village planning and implemented in conjunction with parking reforms and transportation demand management strategies. They are most cost effective if build in compact urban villages with at least 25,000 residents and employees located within its walkshed. Their costs can be paid through value capture, with connection fees or special taxes.

The main obstacle to comprehensive pedway development is the well-entrenched biases that favor motorized travel and undervalue non-motorized modes in transportation planning and investment. Transportation agencies have tools for planning and evaluating roadway improvements, and funding to implement them, but lack comparable tools and funding for walkability improvements such as shadeways and pedways, even if they are more cost effective and beneficial than roadway projects.

The Cool Walkshed Index (CWI) is a practical way to evaluate walking facility thermal comfort. It can be used to rate hot weather pedestrian access to a building or in area, to identify problems, and to set improvement targets. Currently, most urban buildings and neighborhoods have CWI E (incomplete sidewalk networks) or D (complete sidewalk networks). Those in moderate-heat cities should aspire to CWI C (shade sidewalks on busy routes); those in high-heat cities should aspire to CWI B (enclosed, climate-controlled pedways within a 300 to 1,000 foot walk); and extreme-heat cities should aspire to CWI A (enclosed, climate-controlled pedways connected to most residences and worksites).

Shadeway and pedway development can substantially improve the walkability of millions of urban neighborhoods, and the lives of billions of people.

Resources

ADUPC (2009), Abu Dhabi Urban Street Design Manual, Abu Dhabi Urban Planning Council.

ADUPC (2010), Abu Dhabi Urban Public Realm Design Manual, Abu Dhabi Urban Planning Council.

Justin Boyar (2016), Walkability: Why it is Important to Your CRE Property Value, JLL Real Estate.

Debra Efroymson (2012), Moving Dangerously, Moving Pleasurably: Improving Walkability in Dhaka: Using a BRT Walkability Strategy to Make Dhaka’s Transportation Infrastructure Pedestrian-Friendly, Asian Development Bank.

Gehl Architects (2013), Istanbul: An Accessible City – A City for People, EMBARQ Turkey.

Becky P.Y. Loo (2021), “Walking Towards a Happy City,” Journal of Transport Geography, Vo. 93.

Todd Litman (2022), Cool Planning for a Hotter Future, Planetizen.

Todd Litman (2023), Evaluating Active Transport Benefits and Costs, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

NACTO (2016), Global Urban Street Design Guide, National Association of City Transportation Officials.

Anna Ponting and Vincent Lim (2015), Elevated Pedestrian Linkways — Boon or Bane?, Centre for Livable Cities.

Michael A. Rodriguez and Christopher B. Leinberger (2023), Foot Traffic Ahead: Ranking Walkable Urbanism in America’s Largest Metros, Smart Growth America.

Paula Santos (2015), The Eight Principles of the Sidewalk: Building More Active Cities, The City Fix.

Walkability Asia supports walkability improvements in Asian countries.

USEPA (2022), National Walkability Index, US Environmental Protection Agency.

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.