Governor Kathy Hochul’s ambitious proposal to create more housing has once again run into a brick wall of opposition in New York’s enormous suburbs, especially on Long Island. This year, however, the wall may have some cracks.

For the second year in a row, New York Governor Kathy Hochul has proposed badly needed but politically unpopular statewide land use reforms to spur the construction of more homes, and for the second year in a row the fate of her proposal will likely be decided in the state’s enormous and provincial suburbs, including Westchester County to the north of New York City and Long Island to the east.

Led by lawmakers from these suburbs, the State Assembly and Senate each released their own budgets on Tuesday, known as “one-house” proposals, which effectively neuter Hochul’s plan. Now, Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, Assembly Majority Leader Carl Heastie, and the Governor—the proverbial “three people in a room” as New York politicos say—will negotiate their proposals and aim to finalize the state budget by the April 1 deadline.

The wide gulf between the Governor and the legislature suggests Hochul’s New York Housing Compact as originally written will not become law. Yet the legislative budgets do make room for some statewide housing changes. And in any case, Hochul is standing her ground in the face of the opposition and touring the state to raise support for the Compact. It appears New York’s housing framework will change this year, but how and how much now depends on the raw political will of the newly-elected executive.

The New York Housing Compact

The New York Housing Compact would remove barriers to housing production, incentivize new construction, and set local housing targets across every New York community to lay the groundwork for 800,000 new homes statewide over the next 10 years, which is more or less the amount required to keep pace with job and population growth.

The Compact would require every community to grow its housing stock over the next three years—by 1 percent in upstate communities and 3 percent in downstate communities—which would amount to less than 50 new homes for 80 percent of localities outside New York City.

If communities do not meet these targets after three years, proposed housing developments that meet particular affordability criteria, but may not conform to existing zoning, can take advantage of a fast-track approval process by appealing to a new State Housing Approval Board. (A similar “builder’s remedy” exists in neighboring Connecticut).

The plan also requires all communities with a rail station (the lower Hudson Valley, Long Island, and New York City) to undertake rezonings that allow for higher density housing within a half mile of the station.

The Compact would provide $250 million for infrastructure upgrades to support new housing, $20 million for planning capacity, $50 million for home repairs in under-resourced communities of color, as well as property tax exemptions that encourage affordable housing construction and rehabilitation.

New York State has never had a statewide framework for housing growth and has always been exceedingly deferential to the “home rule” of municipalities. Unsurprisingly, while the state created 1.2 million new jobs in the past decade, it created only 400,000 new housing units. As a result, more than half of New York renters are rent-burdened, spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent—the second-highest rate in the nation.

Residents appear to be feeling the squeeze and voicing their support accordingly. An early March poll conducted by Slingshot Strategies finds 77 percent of likely New York voters agree the state is facing a housing crisis, 74 percent support reforming the housing approval process, and 65 percent support imposing housing production targets on towns and cities. Another from Data for Progress finds that 67 percent support legislation that promotes transit-oriented development, including 70 percent of voters in the Mid-Hudson region and 66 percent on Long Island.

Their representatives are less enthusiastic.

Legislators and local officials respond

The Compact is more far-reaching, comprehensive, and thought-out than Hochul’s modest 2022 proposal to legalize accessory dwelling units as-of-right statewide, which aroused the interest of planners and policy wonks but failed to catch on with the general public. Both, however, provoked widespread and vitriolic opposition from municipal and state officials in the New York City suburbs.

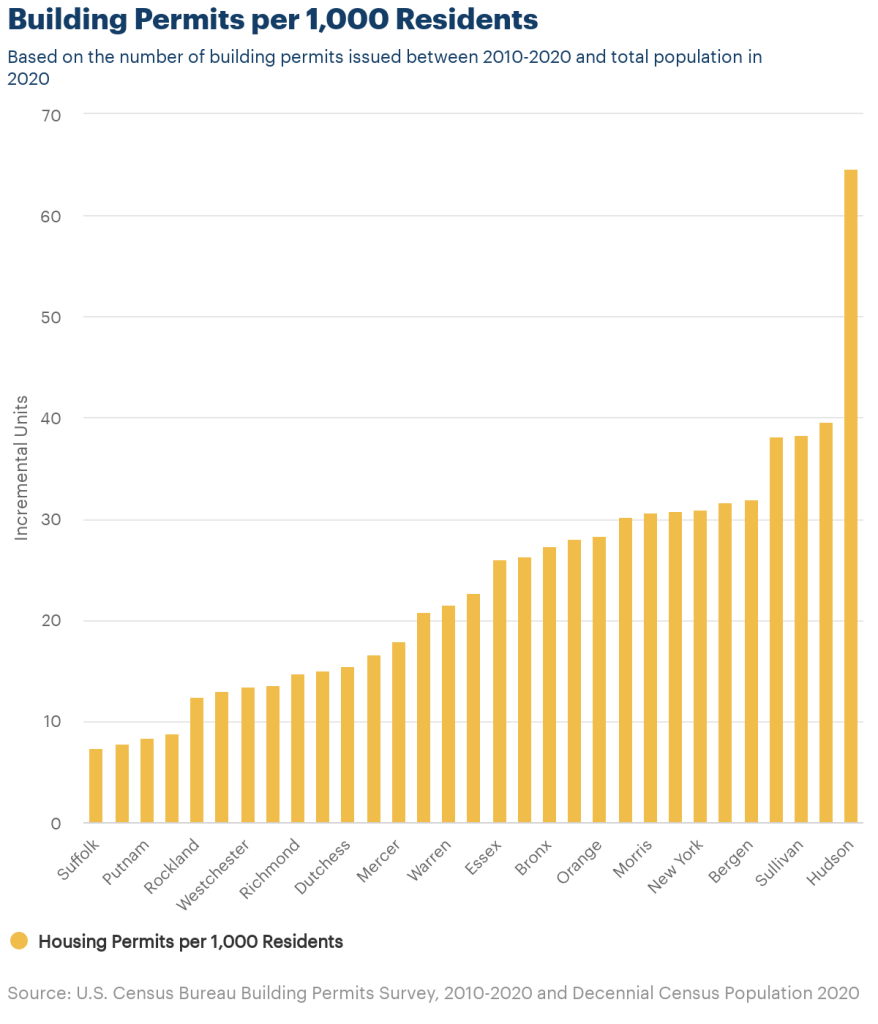

Nowhere is the opposition more fierce than on Long Island. The thin, long, parochial, and geographically-isolated region is made up of two counties, Nassau and Suffolk, that permitted fewer new homes than any other county in the entire tri-state region over the last decade, less than 10 new homes per every 1,000 residents.

“Albany is trying to steal your zoning and force something down your throats,” said Hempstead Town Supervisor Dan Clavin during a press conference in the driveway of a single-family home in January. “We want local control, not Hochul control,” said State Senator Patricia Canzoneri-Fitzpatrick during a press conference at a Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) station in March.

“Her plan would create high-density housing zones around every Long Island Rail Road station and allow apartments to flood single-family home neighborhoods throughout the Town of Oyster Bay. This means that THOUSANDS of new apartments, people and cars could flood YOUR neighborhood and YOUR block,” reads a newsletter sent by the Town of Oyster Bay to residents. (To achieve the Housing Compact’s growth targets, Oyster Bay would need to add approximately 87 new homes.)

Republican Nassau County Executive Bruce Blakeman, who flipped his seat from blue to red in 2021, suggested Democrats would face tremendous political consequences, a “suburban uprising”, if land use changes go through.

These officials have not proposed other tangible means to make it easier to live on Long Island, where the cost of housing has increased more than 66 percent over the last decade excluding the East End. Even liberal assessments of Hochul’s proposal which acknowledge the severe housing crisis don’t offer concrete solutions and instead fall back on non-committal language. “We will identify areas for future housing development and encourage the re-development of under-utilized properties [italics mine],” writes Dave Calone, candidate for Suffolk County Executive, about a hypothetical counter-plan.

To be sure, pockets of opposition large and small exist across the state, including Westchester County, but the most vocal and politically consequential resistance comes from Long Island, home to nearly eight million people and many swing voters.

Predictably, the legislative budget proposals reject Hochul’s ideas. Both one-house budgets maintain the housing targets, but remove the state’s ability to enforce them by overriding local zoning rules. They also call for doubling state incentives to $500 million. Democrats hold a supermajority in both houses, but the Housing Compact faced criticism not just from the right, but from the left and labor, too, for its perceived lack of affordability requirements and explicit worker protections, respectively.

“For us, who want what the governor wants, we believe that there can be a more collaborative and inclusive way to get there,” said Stewart-Cousins, who represents portions of Westchester County. “Now, ultimately, who knows what the resolution will be. But the involvement of local communities as we get there is extremely important.”

A second chance for success

The situation in the suburbs echoes the 2022 legislative session.

Last year, Nassau County Democrat Tom Suozzi latched onto the Governor’s proposal as a wedge issue in his primary campaign against her, rallying to his banner the white, middle-aged, and primarily male town supervisors and state legislators of Long Island (both Democrats and Republicans). Even those who may not have opposed Hochul’s proposal were neutralized: virtually no supervisor or state elected on Long Island supported the plan save for Assemblymember Phil Ramos (D-Brentwood).

In Newsday, Ramos minces no words about his frustration with his fellow lawmakers.

“‘Local control’ has been code word for a long time, for shutting out people of color in certain communities. [Hochul’s] efforts to increase affordable housing in various towns–not just certain areas–will diversify Long Island, which is very segregated. You know when we hear pushback against affordable housing, we hear a lot of other buzzwords as well…To people in diverse communities, we know all too well what community character they’re referring to.”

In 2023, opposition on the island has been less monolithic. The Governor secured the critical support of Suffolk County Supervisor Steve Bellone, as well as a few local elected officials like the Mayor of Patchogue. Hochul held an event with both in late February to promote the Compact. The grassroots support is also more visible in 2023. Housing advocates led by Pilar Moya of Housing Help held a rally in the freezing cold in Garden City to support the plan. In 2022, these groups and others were outpaced by the opposition and could not muster a press conference before Hochul dropped her housing plan.

Buoyed by these developments, Hochul remains resolute. “It would be so much easier to say someone should fix that some day … But that’s not who we are,” the governor said on Wednesday during a community roundtable about her housing proposal in Rye Brook with business owners and elected officials from across Hudson Valley. “We’re going to look back and say not only did we meet the moment—we exceeded the moment.”

Hochul has gotten much farther than she did last year, and she appears to have on her side both public opinion and the moral high ground. As the tri-state think tank Regional Plan Association has shown, single-family zoning is directly correlated with segregation throughout the New York City metro area. By arguing against the growth of even marginal amounts of multi-family housing, local officials are de facto arguing for segregation whether they realize it or not.

Regardless of their motives, generations of local officials have failed to provide for New York’s housing needs at scale. That’s because as local officials, they cannot by their nature provide housing at scale: that’s why a statewide framework is advantageous. As Hochul says, "we have tried the ‘do-it-on-your-own’ for generations."

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.