Some highway advocates continue to claim that roadway expansions are justified to reduce traffic congestion. That's not what the research shows. It's time to stop obsessing over congestion and instead strive for efficient accessibility.

There are two contrasting perspectives concerning traffic congestion problems and solutions.

The old perspective assumes that traffic congestion is our worst transportation problem and that roadway expansion is the preferred solution. It evaluates transportation system performance based on congestion indicators such as roadway level-of-service (LOS) and the Travel Time Index and prioritizes transportation investments based on their purported congestion reductions. If you love to drive and work in the automobile or highway industries, you love this perspective.

The other perspective considers traffic congestion just one relatively modest of many transportation-related problems. For example, INRIX claimed that in 2018 congestion cost “each American” 97 hours of additional travel time worth an estimated $1,348 annually, but these figures really refer to approximately 15-25 percent of all Americans who are urban-peak auto commuters. The Texas Transportation Institute’s Urban Mobility Study estimated that in 2017, U.S. congestion costs totaled $166 billion, which averages about $500 annually per capita, but both of those studies use assumptions that tend to overestimate true congestion costs—they use free-flow travel time as a baseline, so much of their congestion “costs” are simply motorists reducing their speed to legal limits, and they assume very high travel time unit costs which are far higher than most motorists are actually willing to spend for travel time savings. More realistic estimates indicate that congestion costs probably average between $200 and $600 annually per U.S. motorist, depending on assumptions.

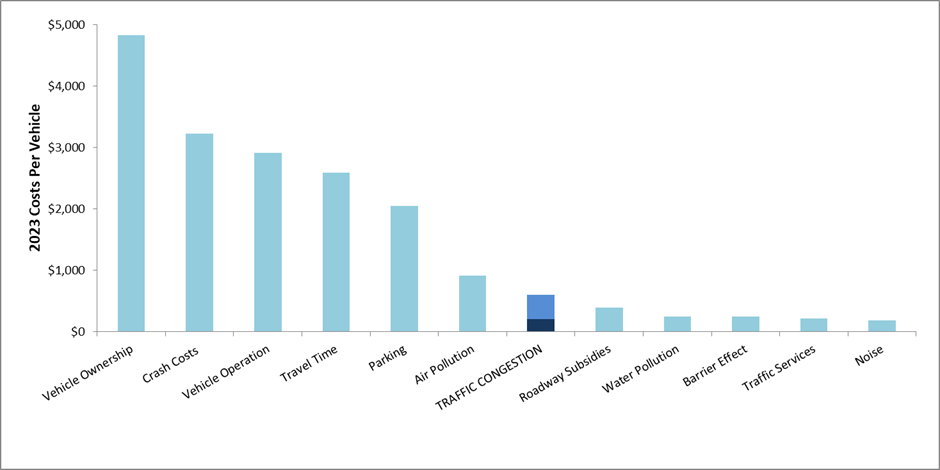

The figure below compares these estimates with other vehicle costs. This indicates that congestion is a moderate cost, much smaller than what motorists spend on vehicles maintenance and other costs, what governments spend on roads, what businesses spend on off-street parking facilities, and much less than traffic crash costs.

Estimated annual vehicle costs per vehicle

This has important implications for congestion reduction analysis. It indicates that a congestion reduction strategy is worth far less if it increases other transportation costs, and worth far more if it reduces them. For example, since urban highway expansions induce additional vehicle travel, they tend to increase the costs of downstream traffic and parking congestion, crashes, pollution, and sprawl-related costs, reducing their net benefits.

On the other hand, improving resource-efficient modes such as bicycling, ridesharing, public transit, and telework, and boosting TDM incentives that encourage travelers to use those modes, provide additional benefits in addition to reducing congestion; they reduce downstream congestion and infrastructure costs, consumer costs, accidents, and pollution emissions, while also providing independent mobility for non-drivers and improving public health. As a result of those large and diverse co-benefits, TDM solutions are worth far more than just their congestion reductions.

This is a timely issue because some planning professionals continue to apply incomplete analysis to highway expansion projects. For example, you may have read Steven Polzin’s recent Planetizen blog, “Induced Travel Demand Induces Media Attention,” which criticized news media for giving excessive attention to induced travel impacts, and my subsequent column, “Should We Continue to Ignore Induced Vehicle Travel Costs?” which critiqued it.

I described some of the many professional studies indicating that induced travel fills most added urban highway capacity within a few years, degrading any congestion reduction benefits, and that induced vehicle travel imposes significant costs. These studies conclude that transportation professionals would be negligent to ignore these impacts when evaluating congestion reduction options.

I tried to make my column humorous; Polzin found my sarcasm offensive, so I apologized for any offense, but that does not change my message; ignoring induced travel reflects outdated planning practices and is therefore unprofessional. Let’s take a serious look at this issue.

My report, Generated Traffic and Induced Travel: Implications for Transport Planning, provides an overview. It was controversial when first published in the ITE Journal in 2001, but since then there has been lots of excellent research supporting its conclusions. For a good technical summary read Calculating and Forecasting Induced Vehicle Miles of Travel Resulting from Highway Projects, produced by an expert panel for the California Department of Transportation.

One finding from this research is that much of the vehicle travel induced by urban fringe highway expansions occurs on other roadways, because those highways stimulate more sprawling development. One recent study found that each 1 percent increase in highway lane-kilometers typically increases total vehicle kilometers by 1.2 percent with a much smaller effect in cities with road pricing and high-quality rail transit; a 1 percent increase in lane kilometers increases congestion by 1.9 percent in cities without highway tolls but only 0.3 percent in cities with tolls; a 1 percent increase in railroad network length decreases congestion by 0.6 percent to 1.3 percent, depending on rail service quality.

A recent study by Professor David Metz, “Economic Benefits of Road Widening: Discrepancy Between Outturn and Forecast, compared predicted and actual traffic volumes and speeds after the expansion of London's M25 motorway. The project was justified on the basis of predicted speed improvements that did not actually occur. Had planners been more skeptical and rational, the government would have invested in other, more effective transport improvements. This should not happen.

The National Center for Sustainable Transportation’s Induced Travel Calculator, and other models, can be used to predict the incremental vehicle travel induced by urban roadway expansions.

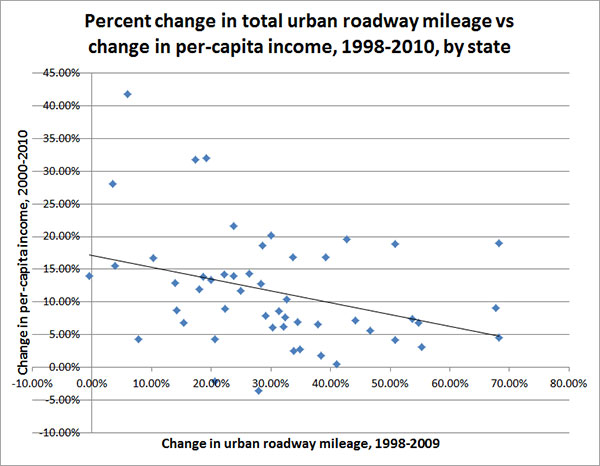

Induced travel is not bad, but it is costly, including external costs that motorists impose on other people. It also fails to provide the economic benefits that highway expansion advocates claim. In fact, highway expansions are associated with reduced economic productivity, as illustrated below.

Economic theory suggests that travelers should have all of the road space that they are willing to pay for. That would typically mean tolls of $0.50 to $2.50 per vehicle-mile on expanded urban highways. However, as Joe Cortright shows in his column, How to Solve Traffic Congestion: A Miracle in Louisville?, even modest tolls significantly reduce traffic volumes, indicating that motorists are very price sensitive, so few are willing to pay cost-recovery prices.

It is time for planners to rethink the way we evaluate congestion problems and solutions. Vehicle travel is not an end in itself; our ultimate goal is to improve accessibility. Traffic congestion is one constraint on accessibility, but others are more important. For example, the study, “Does Accessibility Require Density or Speed?” found that a given increase in urban density, and therefore proximity, has a far greater impact on overall accessibility than an increase in travel speed, and therefore congestion reductions. This is particularly true of disadvantaged groups who cannot drive or are financially burdened by vehicle expenses.

It is irresponsible for transportation agencies to expand highways in ways that contradict other community goals. If they do nothing, at worst, traffic congestion will maintain equilibrium; people will manage within its constraints. Even better, transportation agencies can invest in resource-efficient alternatives—better walking, bicycling, public transit, and telework opportunities—that improve accessibility, increasing transportation system efficiency.

If we truly want to truly optimize our transportation systems, we need a more comprehensive analysis of impacts and options, including the full costs of urban highway expansions and the full benefits of non-auto mode improvements and TDM incentives. Highway expansion should be a solution of last resort, only implemented when all other solutions have failed and users are willing to pay the full costs through tolls.

It's time to stop obsessing about congestion and instead strive for efficient accessibility that serves everybody in the community.

For more information:

James Brasuell (2022), Planning for Congestion Relief, Planetizen.

Joe Cortright (2021), How to Solve Traffic Congestion: A Miracle in Louisville?, City Observatory.

Elizabeth Deakin, et al. (2020), Calculating and Forecasting Induced Vehicle Miles of Travel Resulting from Highway Projects: Findings and Recommendations from an Expert Panel, California Department of Transportation.

ITF (2021), Decongesting our Cities Summary and Conclusions, International Transport Forum.

Todd Litman (2020), Generated Traffic and Induced Travel: Implications for Transport Planning, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

David Metz (2021), “Economic Benefits of Road Widening: Discrepancy Between Outturn and Forecast,” Transportation Research Part A, Vo. 147, pp. 312-319.

Jamey M.B. Volker, Amy E. Lee and Susan Handy (2020), “Induced Vehicle Travel in the Environmental Review Process,” Transportation Research Record (doi:10.1177/0361198120923365).

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.