The updated version of Donald Appleyard’s 1982 book Livable Streets, written by Appleyard's son, dives even deeper into the ‘ecology of the street,’ proposing actionable solutions for the conflicts and problems facing urban environments today.

More than four decades after the publication of the original Livable Streets, Bruce Appleyard revisits the concepts laid out by his father in his seminal work, expanding on Appleyard’s analysis of how cars and car-oriented design impact people and cities. What qualities make streets comfortable? What makes pedestrians feel safe and empowered, willing even to let their children walk or bike to school? Bruce Appleyard explores these questions and more, tracing the connections between street design, power dynamics, congestion, and other pressing and intertwined problems. The excerpt below introduces the book.

In 1969 when I was 4 years-old, I was hit by a car and nearly killed.1 Around that time my father, Donald Appleyard, started work on what would become published in Livable Streets in 1981 – a ground-breaking and seminal work, the product of more than a decade of rigorous research and thoughtful analysis that would uncover the ill effects of traffic and lay out the seminal arguments that streets are for people.

On September 23, 1982, a year after Livable Streets was published, my father was killed by a speeding, drunk driver in Athens, Greece–iy was never reprinted. My father’s untimely death at 54 was not only extremely painful for me and my family—I was seventeen at the time—it was also a devastating loss for those concerned with the design, planning and engineering of our streets, as well as the “thousands of people who may not have known him but whose environments and lives are more joyful and satisfying because he helped plan them—humanely.”

As I clawed back from this tragedy, there was something that always deeply resonated with me about Livable Streets which allowed me to reconnect with my Dad throughout the years. While one might look at diaries or letters of lost loved ones, I had a book filled with my father’s caring expressions of concern for the welfare of children in and around our streets and cities. As I poured through my father’s work, I began to realize that he had actually been inspired by critical events in my own life.

And so it goes, a seminal work on the harms of cars and traffic was book-ended by two terrifying acts of traffic violence. Along these lines, Livable Streets served as a lasting touchstone for me and many throughout the world I am happy to present to you an updated version of the book in Livable Streets 2.0, at almost double the length of the original at 610 pages with revised and expanded content (especially on bicycling and walking), and focusing on four key parts: the conflict, power, promise, and future of our streets.

New Beginnings

Have you ever walked along a street with heavy traffic, and all you could think about were cars roaring by? Have you ever tried to cross a street and a driver refused to stop or even look at you, treating you like you did not belong there? These are not livable streets.

How about when you walk down the street with a young child and you hurry to grab their hand because of the fear of traffic nearby? This is not a livable street.

But, have you ever been on a street that makes you feel relaxed, comfortable, emboldened even? Where you feel free to let your child's hand go to freely explore their world? Where you feel OK about letting them bicycle or walk to and from school? An equal partner with others in the dynamic choreography and “ballet of the street”? These are characteristics of livable streets.

To understand this, we need to understand the conflict, power and promise of the street environment and all that makes it what it is—the street design, the urban form, the land use activities, and the laws, professional practices, and even the institutional and socio-cultural norms that shape them. In the book Livable Streets 2.0, this is referred to as the “ecology of the street” or simply the “street ecology”—and the issues of conflict and power are addressed to understand the problems in this ecosystem to then realize the promise of our streets.

Livable Streets 2.0 deals with ways to solve these problems by realizing the promise of what streets can become through principles, processes, and prescriptions to support walking, bicycling and living — to reimagine streets that help us find peace, rejuvenation, and joy; to engage in enriching exchanges with others; to access opportunities that instill meaning, fulfillment and hope in our lives. Livable streets also allow us to support those we care about, and the world itself – as streets that are more livable and inviting are key to solving problems before us -- from obesity, pollution, congestion, and the climate crisis at hand.

In one of the more memorable passages, we ask about the promise of our streets by saying:

We should raise our sights for a moment. What could a street—a street on which our children are brought up, adults live, and old people spend their last days—where people can move naturally and freely under their own power—and where all are able to celebrate our humanity together—what could such a street be like?

The endurance of livable streets

Throughout my work on Livable Streets 2.0, I have often asked the question “Why did the first edition of Livable Streets resonate so strongly with people when it was first published? And why has it endured over the years?”

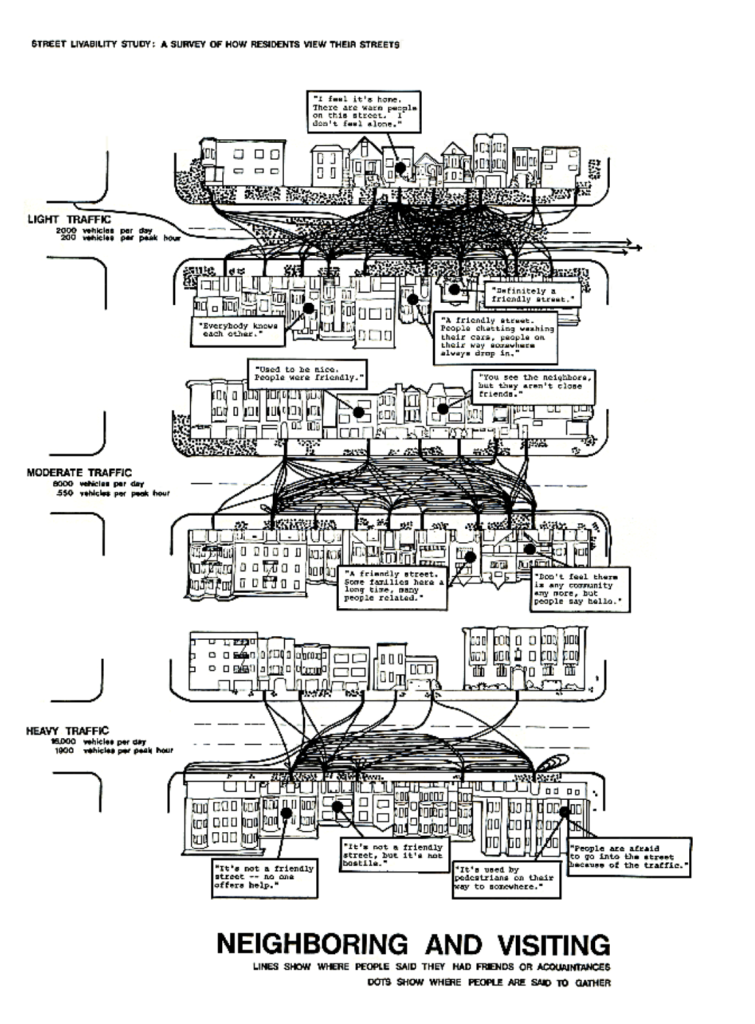

While there may be many reasons, I would like to offer these over all others—this book uncovers, articulates and perhaps more importantly presents in graphic form rigorous research into the conflict playing out in our streets between traffic and people—a power struggle that was felt by many, but until the first edition of Livable Streets, was not fully understood, let alone clearly imagined or pictured. In short, it was the first to use scientific methods to graphically illustrate the invisible harms traffic forced upon people and their communities. Up until then, people likely knew this intuitively, but had not yet fully understood the extent of both the cognitive and community impacts to their environment on top of air quality, noise, etc. Thus, the enduring effectiveness of Livable Streets is conveyed powerfully in figures in Chapters 1 and 2.2

The original Livable Streets revealed to the world, through compelling graphics, rigorous research, and poetic prose, how automobiles degraded the lives of residents in communities and cities. There was also more that needed to be said, however, about the needs of more vulnerable and less powerful groups including pedestrians, bicyclists, people with disabilities, and people of color, as well as how we mediate between competing livability agendas. My work on this new edition builds on decades of researching and working in the field to reimagine and redesign streets to be safer and more livable. The purpose of this article is to place this new work in the field of planning, urban design, engineering, as well as many other academic areas of interest, such as psychology, sociology, anthropology, and now even the world of computer science and artificial intelligence.

As well as being about conflict, power, and promise, at its core, this book is about us—people—human beings and our humanity—and whether or not the street ecology is empathetic, caring, and just. Through this lens, the book focuses on the quality of our lives, relationships and interactions—our experiences—within and around streets—the most accessible public places in our cities—the places for civic engagement, physical activity, meeting neighbors, learning about the world, or simply finding rest and rejuvenation. If I had to sum it up, a livable street restores you. In contrast, an unlivable street drains you.

Along these lines, this book reintroduces the general theory that streets are for people—not merely conduits for cars. This new edition takes this theory even further to argue that streets are places for our humanity, our empathy, and our social equity – from thoughtfully providing for our most natural modes of travel (walking and bicycling), to our ability to equitably access opportunities – spanning from peaceful, restorative, rejuvenation, to equal access to enriching exchanges with others that empower us and our senses of possibility, hope, and joy.

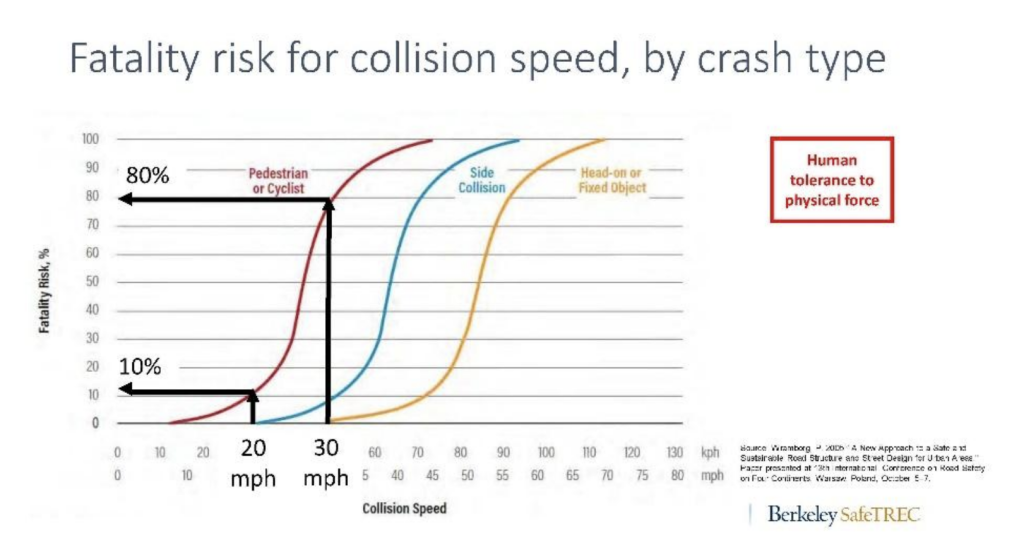

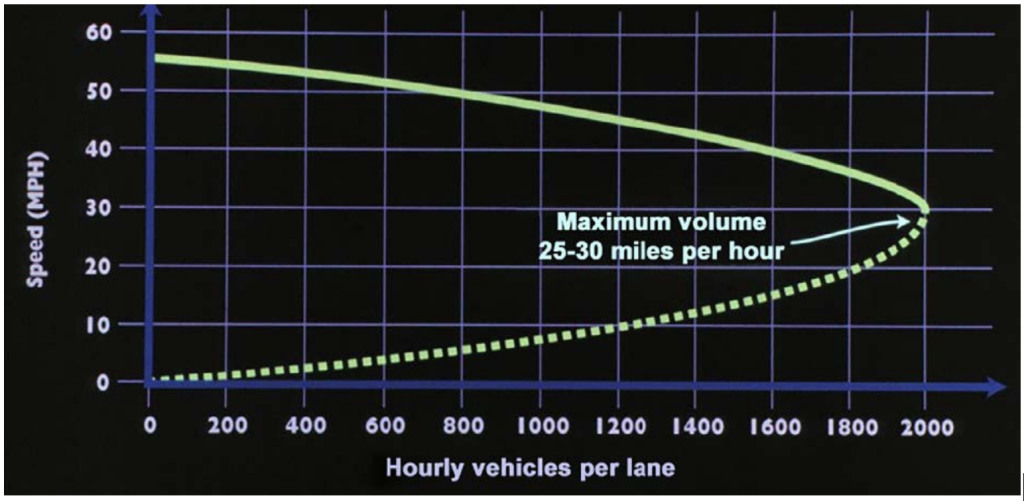

Along these lines, this book argues that we should pivot the planning, design, and operation of our streets around our most natural capacities as human beings—in other words, our humanity. For instance, the chances of being killed as a pedestrian grow exponentially with speed, ramping up most dramatically between 20 and 30 MPH.3In our quest to understand the humanity of our streets, we should ask why might the middle point, 25 MPH, be significant? Is it possible that we, as a species, have evolved to withstand collisions around the fastest speeds we can run? If so, shouldn’t we always argue for lower speed limits based on our physio-biological capacity as human beings? Further, if we can achieve some of the highest vehicle throughputs at around 25-30 MPH on surface streets, is there really any need for much higher speeds anywhere in or around our communities?

In sum, we should let our humanity drive our decisions around our street ecologies rather than some preconceived notions about the needs of machines, and now roboticized automation.4

This book also aims to improve our understanding of what is happening in our streets, offering the most compelling evidence-based arguments for why we should work to redesign them. Further, the analyses, discussions and arguments emerging from Livable Streets are widely believed to have helped lay the foundations for some of our most progressive US movements related to the redesign of our streets, including:

- The Complete Streets Movement

- Safe Routes to School and Safe Routes to Transit Movements

- Context Sensitive Design Solutions

- Multimodal Level of Service

- Vision Zero Movement

Maintaining its progressive voice of the 1960s and 1970s, this new edition points out injustices and presents ways to address them; to improve our world; to fight for equality and our humanity, now and into the future, in and around our city’s most accessible public spaces—our streets.

1I had slipped out of the back garden, and gotten all the way down to the neighborhood grocery store, about a half a mile from my childhood home. As I crossed a four-lane street, I was hit by the car & driver. After about 24 hours in a Coma, I recall waking up as I was being wheeled through Kaiser Hospital in Oakland for another test. I stayed there, alone, for about a week under observation—which at 4 years old seemed worse in some ways than the collision itself.

2And large credit is due to the remarkable skill of the illustrator, Betty Drake.

3Further accentuating this dramatic increase beyond 25 MPH, Speck (2018) points out that being hit at 20 mph equals falling from a second floor, which you may be able to survive, but being hit at 40 mph equals falling from the seventh, which will likely prove fatal.

4Further, if we can achieve some of the highest vehicle throughputs at around 30-35 MPH on surface streets, is there really any need for much higher speeds anywhere in or around our communities?

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.