Opinion: As autonomous vehicles continue to appear on roads around the world, planners and engineers must be proactive in devising new and creative uses for soon-to-be-obsolete urban parking.

When it comes to parking, some of the brightest individuals on the planet can behave in very irrational ways. Instead of utilizing the ample parking spaces in lots and garages near their destination, they will wait and idle for a space close to their destination or drive around "cruising." At the center of this behavior is the belief in a right to free or cheap parking—even in cities where the costs to construct such a space are continually skyrocketing. As a result, the financial outcome for most cities is unsustainable—environmentally or economically. Many experts have talked about the irrationality related to parking resource allocation decisions and how subsidizing space is “bad for everyone.” Most acutely the high cost of providing spaces in parking structures (particularly in commercial areas) is rarely met by parking revenues and as a result these spaces require deep subsidization. (See Evan Goldin’s excellent short summary of Donald Shoup’s The High Cost of Free Parking.)

Yet parking in the urban context of the autonomous future will require vehicle “storage” in a much different way than we currently contemplate it. The proliferation of autonomous vehicles (AVs) will require planners and policy makers to fundamentally change the way they think about parking. Don’t worry; keep calm and carry on. It is just the end of parking as we know it. In the meantime, we put forth two core ideas that will help city officials prepare for this important transportation transition: 1) considering how the development of AV technology will result in reduced auto ownership and 2) thinking about parking demand planning and their relations with land use.

First, with regard to the technology, many experts believe auto ownership has peaked, and it is highly likely that fully autonomous vehicles could be “procured” in quite different ways than current vehicles. This difference will be driven by use patterns that maximize revenue to offset costs. For instance, the combination of multiple LiDAR sensors, radar, cameras, and other additional technological and security features (way beyond that of an average vehicle) mean that the cost of manufacturing an autonomous vehicle is quite expensive—and the cost of owning one prohibitively so.

Based on this cost structure, companies like Cruise and Waymo are using investment capital to pursue fully autonomous (level 4 and 5) driverless vehicles that can be used for fleet-based service; not partially autonomous (level 2 or 3) technology. As a result, these AV companies are experimenting with different ownership models. The predominant use to emerge in these expimeriments are fleets or rideshare arrangements. This is different than the for-sale model of companies like Tesla, which has only been able to produce partially automated technology. Even in a future with some owned AVs, companies like Cruise and Waymo have an incentive to pursue shared ownership or use arrangements to maximize use and related revenues to offset costs.

This cost-use maximization strategy is pragmatic because most vehicles in the United States sit idle for 95% of the time (meaning they are only in use one to two hours in a day). From a parking perspective, a reduction of idle time through the use of shared fleets does not match up to the way we currently think about parking projects, particularly at the household level. In most cities across the country, zoning typically provides for a minimum of one to two enclosed parking spaces per housing unit. This 2-to-1 ratio means that if you were to own even a quarter of an autonomous vehicle, you would still be required to have one to two parking spaces in your house. These zoning regulations imply that cars need to be parked at home as well as a work or school location to provide service, but this assumption could become obsolete as adoption of autonomous vehicles grows.

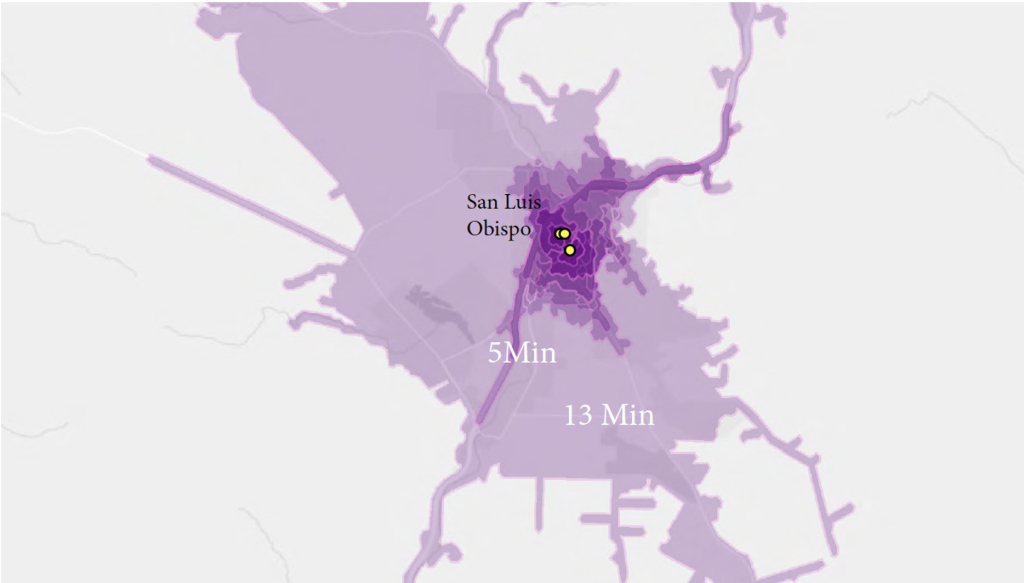

A few years ago, one of us (Riggs) had some students conduct a Geographic Information Systems (GIS) pilot project to investigate potential geographic areas that could be serviced by autonomous vehicle (AV) technology. The project used a central site in downtown San Luis Obispo, California as a primary destination and origin for autonomous vehicle rides. Fast forward a few years, and a multi-million-dollar parking structure is being planned at the same location as the pilot project. The pilot program found—as indicated in the graphic below—a large potential catchment area that AVs could service under certain retrieval expectations.

But instead of a state-of-the-art AV hub, another parking structure will be constructed.

Using a five- and ten-minute network buffer, cars could be located (or stored) as far as ten miles away and still be retrieved on demand. If a system like this could be actualized, it could have many positive implications—including, for example, opening up valuable city center land for better purposes than parking. Most land with the highest value is in the central city. From a planning standpoint, dedicating that land to parking does not mean it is being used for its "highest and best use." This raises the question: Are we on the cusp of a new world, where parking no longer matters in central cities, and can be thought of as facilities where vehicles can go to rest and recharge or get serviced? Moreover, would these facilities only be necessary on the fringe of cities?

Autonomous vehicles could also open up how we think about downtown areas and whether local governments need to be in the business of providing large-scale structures and on-street parking. Numerous publications have discussed the cost and trade-offs of building parking from a land use standpoint. The typical cost per space for a structured parking space is around $40,000. Parking rates need to be high to offset the high cost of construction, and some communities question the level of subsidization required to keep off-street parking rates low. These are important transportation and municipal finance debates. However, they will be irrelevant in the new world we are potentially entering. It might be that parking structures are becoming extinct. Do we really need thousands of downtown parking spaces if we have shared AVs that can pick users up in a matter of minutes?

This leads to a second key consideration for planners and engineers: thinking about parking demand planning and their relations with land use. Planning for construction of new downtown parking is a large part of what some transportations consultants do, but what if we don't really need that downtown parking? As a planning commissioner, one of us (Riggs) was in the position of approving a large parking structure not only in the drop-off location in San Luis Obispo but in the California Avenue area of Palo Alto. Will this kind of structure be needed in the long term? That remains to be seen, but some academics argue that cities might be headed for a decrease in demand by as much as 90%.

These kinds of examples leave transportation planners and policymakers facing tough decisions, but if one thing is clear: the status quo is not an option. Local planners, engineers, and policymakers need to begin rethinking capital investments for parking infrastructure, particularly those that involve long-term debt and bond issues. Maintaining a less than ideal status quo may be better than taking on a more-risky proposition of stranded parking assets in the long term. Likewise, planners and transportation engineers need to begin thinking differently about parking standards and structure design, just like they need to begin thinking differently about roadway and configuration. Businesses might not need six parking spaces per thousand square feet of retail space. Likewise, homes might no longer need a garage, which in turn could make housing construction cheaper or offer more living space in existing homes. Moreover, new parking structures need to be designed differently. They can be planned to transition to “restaurants, bars, apartments, condos and experiential spaces like galleries, museums, concert halls and more.”

Most importantly, as parking space occupancy declines, cities must begin to think about how they adapt on- and off-street parking spaces to new creative uses. While many mall parking lots have begun to contract with electric vehicle (EV) providers to provide destination charging (and expanding this idea might coalesce with greater EV adoption), there are still creative ideas needed for these legacy locations. Perhaps these locations can become livable, linear parks or green roofs, similar to experiments in Colorado and in Texas. Researchers in the UK have been looking into how garages can be used on a wider scale for urban agriculture. In Paris, underground parking is being used for mushroom cultivation. Perhaps former parking garages can become prefab ghost kitchens (as seen here and here) or dwelling units. There are even concepts being thrown out for vertical skate parks and new ways of thinking about playgrounds.

These ideas are a foundation for how we can make our cities and streets more livable by being smarter about how we use parking and the land it occupies. While these reuse concepts have been percolating since before the pandemic, the pivot toward more work-from-home and the acceleration of autonomous solutions makes them more relevant. One takeaway is clear, we must take action now—as the autonomous future is coming quickly. In the meantime: keep calm and carry on; it’s just the end of parking.

Dr. William (Billy) Riggs, Ph.D., AICP, LEED AP, is a professor at the University of San Francisco School of Management, and a global thought leader in the areas of future mobility and smart transportation, housing, economics, and urban development. He is the author of the book End of the Road: End of the Road: Reimagining the Street as the Heart of the City. He can be found on Twitter at @billyriggs.

Dr. Bruce Appleyard, Ph.D., AICP, is an associate professor of City Planning/Urban Design at San Diego State University, where he helps people and agencies make more informed decisions about how we live, work and thrive. He is humanist/futurist at the intersection of transportation, urban design, and behavioral economics, crafting articles, workshops, and lectures designed to help people reach their sustainability, livability, and equity objectives. He is the author of Livable Streets 2.0 about the conflict, power, and promise of our streets.

Niel Schrage is a senior at Harvard University studying Government and Data Science and how data can be leveraged to improve the function of government. He is also interested in understanding the potential of governments to enable innovation to occur.

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.