Architects and urban designers justify or explain their work with words, and municipalities govern design with jargon-filled regulations. The outcome is often underwhelming.

When I first visited Rue Sainte-Catherine in Bordeaux, France, there was a festival on the street, one of the biggest I’d ever seen. People were packed shoulder-to-shoulder as far as I could see.

I asked a passer-by what the festival was, and he gave me a confused look. There was no festival, he explained. It is just a great street, and a lot of people like to be there.

There are, of course, many economic reasons to visit a street like Rue Sainte-Catherine, such as working, shopping, eating, or having a drink. But the street owes that success to the fact that people are willing to spend time there. As many struggling downtowns have learned the hard way, for a main street to succeed, it needs to attract people.

This raises a question: if it is possible to create great streets where people love to spend time, why not build more of them? Great streets were, after all, built by humans — not by an alien race. Termites build environments well-suited for termites. Why don’t humans?

I propose an unlikely culprit: words.

Design is visual. Words are not. Yet architects justify their work primarily in words, and municipalities govern design with long lists of regulations, written in words. The outcome is too often stultifying.

In music, art, and surgery, people hone skills that they cannot fully describe in words. We need to learn to train architects and designers the way we train musicians. We need them to become virtuosos at an essential skill we cannot fully teach with books and words alone: to create wonderful places that people love.

Architecture and Design Without Words

When people focus too much on justifying a project in writing, it can distract them from what should be job number one: designing places where people want to be.

In my home city, Halifax, Nova Scotia, architects justified the design for the Halifax Convention Centre (pictured, left) by saying its two towers represent sails, referencing our maritime history. Another team chose copper cladding for Queen’s Marque (pictured, right), they say, to represent a material used on ships. Such symbolism is a nice gesture, but it does not make up for the blankness of each building.

The team who designed Queen’s Marque gave an impressive presentation at Halifax’s Design Review Committee, describing the project’s symbolism and meaning in grand terms, while saying little about the building’s impact on the street. The committee enthusiastically approved the project.

Words get projects approved, and words get attention for architects in magazines and scholarly journals. Naturally, then, architects focus on what they can describe in words. Symbolism, in particular, gets attention. But symbolism alone cannot convince anyone to walk instead of drive. It cannot create a lively street where locals feel comfortable stopping and chatting. It cannot make people feel grateful to be alive, the way a truly wonderful street can.

In contrast, it is hard to describe the stuff that really matters in words. Consider this pleasant little public space below. This would be a fine spot to sip coffee one afternoon, to meet a friend.

But why is it a good place? There is nothing new or exciting about the design. Almost nothing here symbolises anything. One might name the architectural style, but most residents wouldn’t know it. It’d be hard to explain, on the written page, why the windowsills matter, much less the iron bars. One can use adjectives: cosy, warm, pleasant. But if someone claims the scene is not cosy, could you explain why they are wrong?

Yet the place feels comfortable as clearly as a C Major chord feels bright.

There is an uneven battle for attention between the elements of design that are easy to experience but hard to describe, and the elements that are easy to describe but irrelevant to experience. To fix this problem, we, as designers, need to learn to give power back to the non-linguistic parts of our brains.

The Limitations of Speech

Neuroscientist Barbara Tversky underlines the limits of words with a simple thought experiment.

Bring to mind the face of a close friend. Now, try to describe it. Can you use words to convey the image in high resolution, so I could picture your friend too? Do they have any specific bumps on their skin? What is the precise shape of their cheeks? How does each strand of hair fall?

A picture is worth more than a thousand words. You could never transmit a JPG of your friend via words, no matter how long you spoke.

The average English vocabulary is 20 to 40 thousand words, but we can perceive more than 40 thousand details. Language can only convey a small subset of what the brain itself can perceive.

If you try to explain why a public square feels pleasant, it is a bit like trying to transmit a JPG with words. It’s really rather silly. You can perceive it visually in a resolution that is millions of times greater than you can perceive it linguistically, so why measure its value linguistically?

The Wordless Half of the Brain

What precisely are words? They are very useful for some things, but not others. What is the difference?

Neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist finds an answer in an unlikely place. He writes that most vertebrates have two eyes, and each eye has a different job. One of these jobs corresponds to what we use words for — and one of them does not.

The brain’s left hemisphere controls one eye, and when animals look for food, they favour that eye. In The Master and His Emissary, McGilchrist writes that the left hemisphere focuses on slicing and dicing the world into generic, useful categories, like food or tools. In humans, these categories evolved into words.

Categories are powerful. Once we have placed something into a category (like “sidewalk”) we can assign to it any number of generic uses (walking, socializing), requirements (width), or meanings (gathering place).

The utility of categories ends, however, in everything that is not generic: in all the thousands of subtle details that add up to one’s impression of a particular place. While the brain’s left hemisphere focuses on categories, the brain’s right hemisphere, McGilchrist argues, focuses on all these aspects of our environment that are not generic—on everything that resists categorization.

When animals survey their surroundings, looking broadly for opportunities or danger, they favour their right-hemisphere’s eye, gathering an overall impression of a place, rather than slotting it into one category or the other. He argues we have two separate brain hemispheres because these two types of focus are so fundamentally distinct: one divides the world into specific categories; the other processes what is unique in a scene as a whole.

To grasp the difference, consider the sidewalks above and give this a try: identify everything you can put into words, such as pavement, sidewalk, signs, railings, width, style, historic period, symbolism, street name, and so on. Now consider everything you can perceive but cannot name: the precise arrangement of flowers, the exact texture of brick or sidewalk, the palette of colours on each street, or how those grey stairways on the right visually dominate the street. Everything we look at is a mix of the generic and the specific. Both forms of analysis are essential to cognition.

Pedestrians do not perceive their surroundings in terms of generic categories alone. To create great streets, designers therefore cannot rely on generic words alone. One must look at a design and judge whether, as a whole, the elements add up to the kind of place where people will want to spend time. One must use both eyes.

If designers rely chiefly on words, they risk lobotomizing themselves, cutting off the talents of fully half the brain. They risk reducing their abilities to what they can describe in words: symbolism, design principles, zoning codes, and formulaic calculations.

McGilchrist describes the ugly consequences: “an unyielding, inert, confrontational environment of nonliving surfaces, straight lines, concrete masses and largely generic shapes, which are widely experienced as alienating.”

That rings all-too true.

Rigour Without Words

In today’s pop psychology, the left-brain has a reputation for being logical and rational, likely in part because it handles language, and language is associated with reason. The synonyms for “wordlessness,” in contrast, evoke a kind of mystic flakiness: ineffable, indescribable, nameless, transcendent, and beyond words.

The association of language with rigour is misguided. Linguistic thinking can be flaky, and non-linguistic thinking can be precise and exacting. Duany, Plater-Zyberk, and Speck offer this example of an architect getting lost in words while describing a house:

These distortions elicit decipherment in terms of several virtual constructs that allow the house to analogize discourse and call for further elucidation. These constructs are continually motivated and frustrated by conflicts in their underlying schemata and the concrete form in which they are inscribed. They refer to the ideal or real objects, organizations, processes and histories that the house approximately analogizes or opposes.

Words are not inherently rigorous.

Many rigorous skills, meanwhile, are executed without words: think of the musician who plays precisely in tune, the artist who paints a perfect likeness, the surgeon who removes a tumour wedged between two arteries. These crafts are learned through hands-on practice; they cannot be learned by reading books alone.

In the 1700s, a group of German loggers lived in a small community in Eastern Canada called Lunenburg. They had a knack for building beautiful homes, so much so that the village is now a UNESCO heritage site.

.jpeg)

The loggers did not, however, go to university to learn their trade through the written word, and, as far as I know, they did not judge each other’s work in written critiques. Of course they taught each other using words—they didn’t just point at tools and grunt. But they combined language with on-the-job, practical methods for teaching that go beyond words: demonstration, example, practice. Apprentices could learn how to swing a hammer, how to cut a cornice, how to shape a facade, so that together their designs conveyed a certain sense of quality, a precise cultural craft. These are tacet skills that would be difficult or impossible to learn through books alone, but they are certainly rigorous skills.

Consider the proportion of time a violin student spends practising versus reading. Words matter. But words cannot replace the other components of learning.

Rigorous Feedback for Learning

Violin students can consult a tuner to see if they are playing in tune. Artists can see whether their painting looks like their subjects. Surgeons find out quickly if they accidentally poke a hole in an artery. These practitioners can practice wordless skills, in part, because they receive feedback on how they are doing. What objective feedback can architects and urban designers receive ?

This question is particularly important after a century of being told that aesthetic preferences are little more than subjective. We need something to re-establish trust that there is in fact a difference between places people love and those people avoid. We need an objective yardstick.

Jan Gehl offers a simple solution: measure where people choose to spend time, and where they do not.

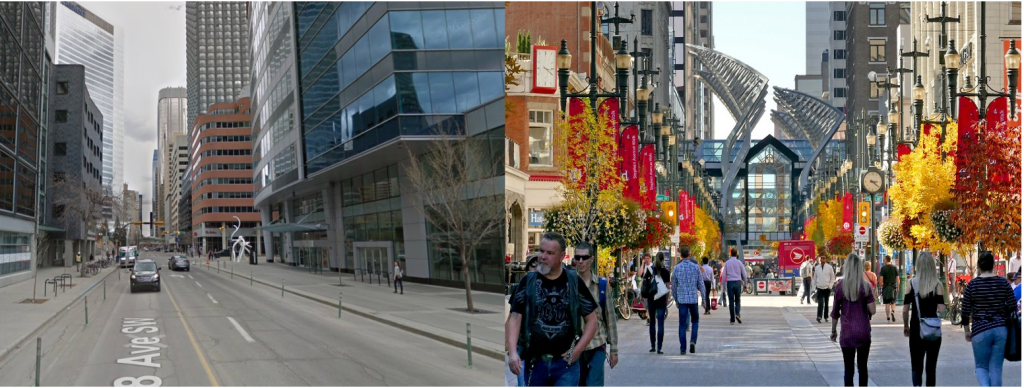

The west end of Calgary’s Stephen Avenue—the photo on the left—looks grey and dull. The east end, on the right, feels bright and vibrant. But these are just subjective feelings. Is there really a difference between them?

Apparently so. In summer, 486 people walk through Stephen Avenue per hour in its west end, whereas 1,176 people walk through the east end, according to an analysis by Jan Gehl’s company, Gehl Architects. More importantly, people are three times more likely to stop, linger, talk, or sit on the east end.

These numbers confirm the rather obvious impression that the east end is more inviting. According to Gehl’s analysis, it is precisely three times more inviting.

With Gehl’s studies, it becomes possible to hold designers to a higher standard. No longer can they simply claim their designs are impressive and effective on paper. They actually need to demonstrate that they have created a place where people want to be. “A public space is not good just because it exists,” Sophia Schuff, one of Gehl’s project managers, tells me in an interview. “A public space is good if people use it.”

A tuner gives violin students objective feedback so that eventually, the student can learn to play without a tuner. Gehl’s studies can serve a similar role for students of people-friendly design. If design students can see and visit places that objectively attract people, and compare these to places that do not, they can begin to develop the ability to recognize the difference. They can begin to see whether a street is “in tune,” so to speak, with human psychological needs.

Where Words Are Best Used

Words are useful for everything that is generic, and some things are generic in people-friendly design.

Human-friendly streets tend to have a few key features that are now widely recognized in the urban design profession. These include: human scale, transparency, complexity, greenery, enclosure, and so on. Enclosure, for example, roughly means that the edges of the street are well-defined by trees and buildings, creating a clear sense of place. The concept helps to explain why this street in Aix-en-Provence, on the left, is more inviting than the one on the right, Herring Cove Road in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Enclosure highlights a key feature to look for. Alan Jacobs travelled the world studying the best streets, and he found that nearly all have a well-defined edge. If someone wanted to make Herring Cove Road a better street for walking, a good place to start would be to establish enclosure with new buildings along the sidewalk.

However, learning the definition of “enclosure” does not imply you have the skills you need to create a well-enclosed street. Some streets create enclosure with buildings, some with a park, some with hedges. On paper, streets may seem to have enclosure but fail to create this sense of place, due to a lack of coherence along the edge or some other issue.

While it is easy to learn the definition of enclosure, it is much harder to learn to recognize and create enclosure. It is, similarly, easy to learn the definition of the term “in tune,” but it is much harder to learn to recognize whether an instrument is in tune, and longer still to play one in tune. (I never quite learned). The word “enclosure” can point you towards something that matters for human-friendly streets, but nonetheless, you need to spend dozens of hours comparing great and terrible streets to develop a sense of what it means in practice.

The same goes for human scale, complexity, transparency, or, more broadly, human-friendly design. Words can point to patterns a designer should learn to recognize. But recognizing these patterns is a skill. Learning definitions cannot replace that skill.

Don’t Forget You Have a Brain

If aliens wanted to build streets that humans would love, they would need to develop complex mathematical formulas to identify the millions of details in a visual scene and predict how the human visual cortex will process these details. To be fully accurate, their formulas would need to be as complicated as the human brain itself.

The job is easier for us. We can use our own brains to see how others will see a street. With a bit of practice, we can learn to pick up on the elements that matter most, and how they fit together.

Our obsession with words has made us blind to the abilities of our own brains to recognize human-friendly places. It’s a skill we need to relearn, so that we can begin, once again, to create beautiful, pleasant streets people love—with consistency and rigour.

It makes no sense that humans so rarely create places that humans enjoy. We are building streets for ourselves, after all. We need to teach human-friendly design as a rigorous skill, so that every single new building, without exception, will contribute to creating streets where people want to be.

Tristan Cleveland is an urban planner with Happy City in Canada and a PhD candidate with Dalhousie’s Healthy Populations Institute.

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.