Compact, walkable urban villages support sustainable economic development by reducing transportation costs, leaving residents with more money to spend on local goods, and by creating more efficient and attractive commercial districts.

True sustainability involves more than just environmental protection: it balances environmental, social and economic goals. There is plenty of guidance concerning how to increase environmental sustainability by reducing resource consumption and habitat degradation and a growing body of guidance for achieving social sustainability by creating healthier and more equitable communities, but there is less guidance on economic sustainability. Let’s start to fill that gap.

Economic development refers to progress toward a community’s economic goals such as increased employment, income, business activity, property development, and tax revenue. My research indicates that a very effective way to achieve these goals is to create urban villages.

What are Urban Villages?

Urban villages are compact, mixed-use, multimodal neighborhoods where most commonly-used services are easy to access by walking, bicycling, and micromodes (e-bikes and e-scooters). There are many types of villages. In rural areas they consist of small towns with 2,000 to 10,000 residents. In suburbs they include walkable, mixed-use commercial districts, sometimes developed around a transit station. In cities they include commercial districts and shopping streets (in England called “high streets”). Their development is sometimes called Smart Growth, New Urbanism, Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), or recently, 15-minute communities.

An urban village should have a Walk Score over 70, indicating that most errands can be accomplished without a car, as indicated below:

Walkscore Ratings

90–100 Walker’s Paradise. Daily errands do not require a car

70–89 Very Walkable. Most errands can be accomplished on foot

50–69 Somewhat Walkable. Some errands can be accomplished on foot

25–49 Car-Dependent. Most errands require a car

0–24 Car-Dependent. Almost all errands require a car

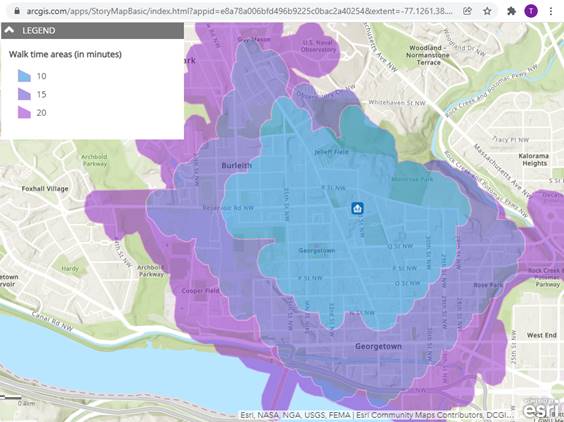

Since most utilitarian walking trips are less than ten minutes in duration an urban village should generally have a radius of less than a half-mile, which we can call the local catchment area, or walkshed (comparable to a watershed that flows into a river). The simplest way to measure the walkshed is to draw a half-mile radius from the village center, indicating travel distances as a crow flies. But as the folks at the ESRI mapping company point out, crows don’t walk, so a more accurate walkshed map is an isochrone showing the area that an average person can walk in a given time period, taking into account sidewalk networks and barriers such as rivers and roads.

Molly Zurn recently described how to do this using free ArcGIS Online (thanks Molly!).

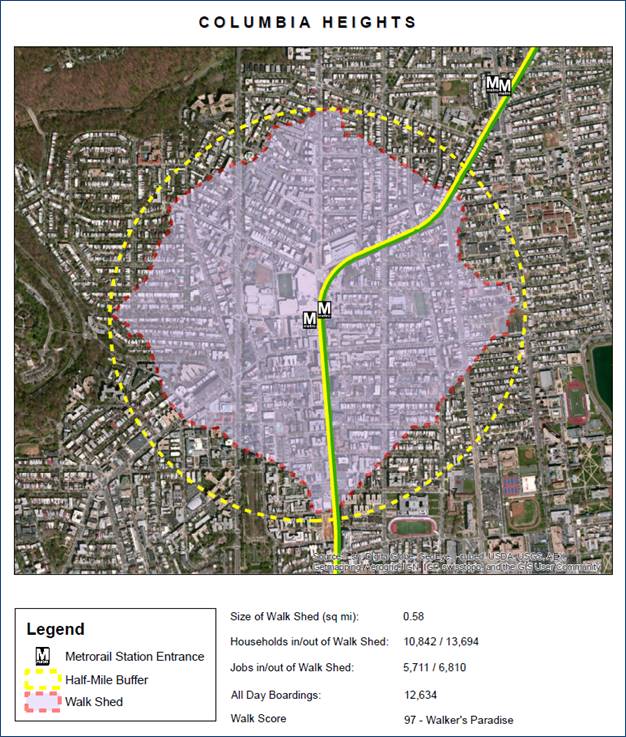

The Metrorail Station Walk Shed Atlas produced by Planit Metro shows walksheds for Washington DC transit stations. Below is the map showing the Columbia Heights station walkshed. This is a classic urban village with a transit station and commercial buildings in the center, surrounded by medium-density residential. The area has a 97 Walk Score, indicating a "walker’s paradise." It contains more than 10,000 homes and more than 5,000 jobs; that’s a lot of wallets!

A typical urban village walkshed contains 300 to 500 gross acres, but a portion of this land area is dedicated to roads and parks, so net developable land is typically 250 to 350 acres. How this land is managed determines the village's economic and social success.

What Does a Sustainable Urban Village Require?

Consumers want goods and businesses want customers. An urban village brings them together to create a mutually beneficial and stable relationship. Everybody wins! To be successful, a village needs an appropriate mix of businesses to serve the needs of nearby employees and residents. An important anchor is a full-service grocery store that provides both affordable and specialty foods (organic, ethnic, etc.), plus a deli, bakery, and a pharmacy either included or nearby. That generally requires a store with a footprint of at least 10,000 square feet.

Such a store and other village businesses typically require at least 10,000 customers. To sustain the local economy, while minimizing local traffic and parking problems, at least half of those customers should be nearby employees or residents who arrive without a car. That is the key to sustainability: a multimodal village reduces vehicle expenses, leaving households with more money to spend on other goods; it reduces road and parking facility costs to local governments and businesses; and it reduces local traffic risk, noise, and pollution, making the village more attractive.

Living within convenient walking distance of a full-service grocery store that sells both affordable and specialty foods is a recipe for health and happiness. Such stores are more economically successful and sustainable if they have 5,000 to 10,000 customers in their walkshed. Urban villages with diverse housing types allow this to occur.

This suggests that a successful urban village requires 5,000 to 10,000 residents, or 2,000 to 4,000 homes, within a 250- to 350-acre walkshed. This typically requires an average of 15 to 40 residents, or 6 to 15 housing units per acre, a density level that does not require high-rise development. Sufficient density can be achieved if a third of developable land is devoted to small-lot single-family housing, a third to 2-3 story missing-middle multiplexes and townhouses, and a third to mid-rise (3-6 story) multifamily. Traditional commercial centers often include some residential above commercial, the next ring consists of midrise multifamily, and the outer ring includes a mix of single-family and multiplexes and townhouses. To support creativity and innovation it’s also useful to include some flexible lofts in a semi-industrial area that can be used, for example, as art or music studios, industrial kitchens, or industrial workshops.

These development patterns are illustrated in Julie Campoli and Alex S. MacLean's wonderful book and website, Visualizing Density, the spectacular 3-D maps produced by Urban Footprint, and images such as the one below of midrise housing from The Urbanist.

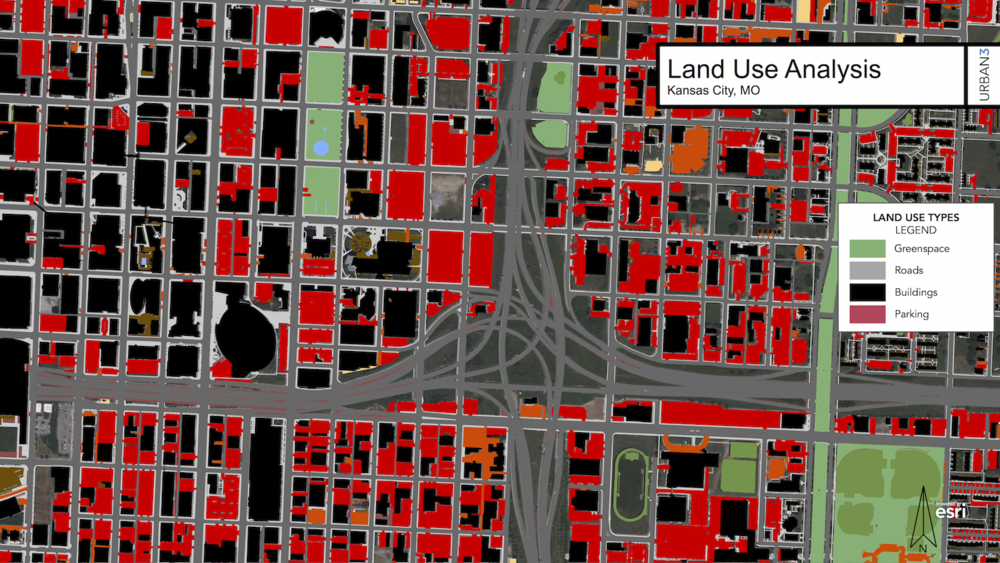

Urban village planning involves trade-offs between people and cars. To be compact, walkable and livable an urban village must minimize automobile traffic volumes and speeds, and the amount of land devoted to parking. Automobile-oriented commercial centers often devote more than half of their land to roads and parking lots, as illustrated below in this map of downtown Kansas City from Daniel Herriges' recent Strong Towns article "Asphalt City: How Parking Ate an American Metropolis". That is ugly and inefficient.

Cars don't have wallets, but people do—so parking lots only support economic development to the degree that they attract more customers than other uses of that land. A multimodal urban village with efficient parking management minimizes the number of parking spaces needed in that area, leaving more land for productive uses. An acre of surface parking can accommodate 250-350 cars, 200-400 employees in mid-rise commercial buildings, or 100-300 residents in mid-rise multifamily housing. A typical downtown employee probably spends about $5,000 annually, and a typical downtown resident probably spends $10,000 annually, at local businesses (cafes, restaurants, and shops). As a result, an acre of village center land that changes from parking to offices generates one to two million dollars in additional commercial activity, and if converted to residential adds one to three million dollars in commercial activity. If the urban village has diverse goods and services, those dollars will circulate several times—economists call this a multiplier—as money spent in one business, say the bakery, is spent by owners and employees in others, such as a nearby accountant, pharmacy, or clothing store.

Sustainable Urban Village Planning Checklist

|

How do Urban Villages Support Local Economic Development?

Let me count the ways!

Residents of a successful village typically own about half as many vehicles and generate half as many vehicle trips than other urban dwellers. More than half of trips are made by non-auto modes, and many car trips are park-once (motorists park and walk to various destinations rather than driving and parking at each). This provides many economic benefits.

Reducing automobile ownership reduces vehicle expenses. Because they require minimal labor input and most of the value is imported from other regions, vehicle and fuel expenditures tend to provide less local employment, business activity, or productivity than most other consumer purchases. Vehicle dealers prep, sell and service vehicles, but those activities represent less than 20% of total vehicle costs, and most fuel sales are now automated, requiring minimal labor. Of each dollar spent on vehicles and fuel, $0.80 to $0.90 typically leaves your community. Most other consumer goods require far more local labor, resulting in much more money circulating in the local economy. A typical family that moves from an automobile-dependent suburb to an urban village will cut its vehicle expenses in half, from about $10,000 to just $5,000 annually, leaving $5,000 more to spend on food, housing, entertainment, and education, goods that generate lots of local jobs and business activity.

Described differently, households located in an urban village typically devote less than 10% of their budgets to their vehicles and residential parking, about half as much as in auto-oriented areas. As a result, urban village residents have about 10% more money to spend on non-transportation goods.

Many people want to live in walkable neighborhoods. The National Association of Realtors' National Community Preference Survey indicates that about half of all households prefer living in a walkable neighborhood close to services, even if that requires choosing a compact house (a townhouse or apartment), and many studies indicate that local property values tend to increase with improved walkability. Virtually everybody benefits if we build more urban villages so any household that wants to can find suitable homes in a walkable, mixed-use neighborhood.

Urban villages also reduce public infrastructure costs. In automobile-oriented areas, where virtually every adult owns an automobile and uses it for most trips, more than half of commercial land is devoted to parking facilities, and parking adds 10% to 20% to building costs. By reducing vehicle ownership and use and creating compact areas where parking facilities can be managed and shared for efficiency, urban villages can reduce these costs.

Because they are more compact and walkable, with lower vehicle traffic volumes and speeds, urban villages tend to be more livable and attractive to shoppers, residents, and sustainable, amenity-sensitive industries, such as professional services and software development, whose employees want nearby shops, restaurants, and childcare.

Numerous studies indicate that compact, multimodal development tends to increase productivity, innovation, and tax revenues. As Joseph Minicozzi described in a Planetizen blog, The Smart Math of Mixed-Use Development, compact development generates more economic value per acre. This not only benefits businesses. A multi-generational study titled “Does Urban Sprawl Hold Down Upward Mobility?” shows that children from low-income families are much more likely to be economically successful as adults if they grow up in compact, multimodal neighborhoods than in sprawled, automobile-dependent areas, because this gives them better access to education and jobs. The study “Does Walkability Matter? An Examination of Walkability’s Impact on Housing Values, Foreclosures and Crime,” finds that more compact, walkable urban neighborhoods have lower crime and housing foreclosure rates.

Urban Village Economic Benefits

|

Because they have diverse businesses and a reliable customer base, urban villages tend to be more economically resilient than more specialized and isolated commercial districts. They have been threatened by automobile-dependency and sprawl, which favored regional shopping centers over local businesses, by catalogue shopping and e-commerce, and most recently by the COVID-19 pandemic which created staffing and supply problems, but none of these threats reduce the value of living and working in a compact, mixed, walkable neighborhood where it is easy to get around without driving.

For More Information

Gabriel M. Ahlfeldt and Elisabetta Pietrostefani (2019), “The Economic Effects of Density: A Synthesis,” Journal of Urban Economics (DOI: 10.1016/j.jue.2019.04.006).

Marlon G. Boarnet, et al. (2017), The Economic Benefits of Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT)- Reducing Placemaking: Synthesizing a New View, White Paper from the National Center for Sustainable Transportation (https://ncst.ucdavis.edu); at.

Nathaniel Decker, et al. (2017), Right Type, Right Place: Assessing the Environmental and Economic Impacts of Infill Residential Development through 2030, Terner Center for Housing Innovation, Next 10.

Reid Ewing, et al. (2016), “Does Urban Sprawl Hold Down Upward Mobility?” Landscape and Urban Planning, Vol. 148, April, pp. 80-88.

Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti (2017), Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation, University of California Berkeley and the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Joseph Minicozzi (2012), The Smart Math of Mixed-Use Development, Planetizen. Also see, Urban3 Lectures.

Todd Litman (2021), Understanding Smart Growth Benefits, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Prince’s Foundation (2020), Walkability and Mixed Use - Making Valuable and Healthy Communities, Knight Frank and Princes Foundation.

Renaissance Planning (2012), Smart Growth and Economic Success: Benefits for Real Estate Developers, Investors, Businesses, and Local Governments, USEPA.

SGA and RCLCO (2015), The Fiscal Implications for West Des Moines, Iowa, Smart Growth America.

Hongyu Xiao, Andy Wu and Jaeho Kim (2021), “Commuting and Innovation: Are Closer Inventors more Productive?” Journal of Urban Economics, Vo. 121 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2020.103300).

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.