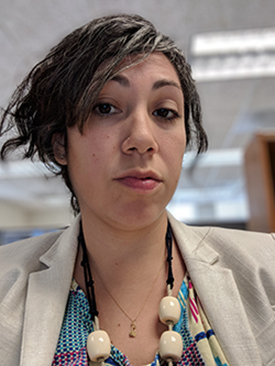

Elizabeth Gallardo is a planning associate with the city of Los Angeles, working as part of an ambitious effort to update the city's numerous community plans while also teaching planning courses at a nearby university.

After graduating with a master's degree in Urban and Regional Planning from Cal Poly Pomona in 2013, Elizabeth Gallardo's career as a professional planner has already resulted in several impactful roles—as a transportation planner at the Los Angeles Department of Transportation, a long-range planner at the Los Angeles Department of City Planning, and as a lecturer at the Cal Poly Pomona.

In this interview, published originally in the 6th Edition of the Planetizen Guide to Graduate Urban Planning Programs, Gallardo discusses the many paths a planning career can take, advice for finding the right path through a planning career, and lessons for connecting theory to practice in the world of planning.

When you’re talking to someone from outside the planning and development field, how do you describe your work?

The easiest way is to say, ‘city planning,’ because people have an idea of what that means. If you say urban and regional planning, no one has any idea. If I go into detail, I say I do community planning that looks at how land uses are arranged spatially in relationship to each other.

How is community planning different from city planning?

A lot of people think, when you say city planning, that you work at a counter. Because Los Angeles is such a big city, we plan differently than most jurisdictions. There is the counter, project planning, and policy planning. Project planning is more similar to the kind of work done at a counter (where you would get a permit to do a residential project), but the projects are larger, discretionary, and require findings. Policy planning (where we do community planning) defines long-range policies and goals for communities. In Los Angeles, community planning also establishes land use plans and zoning.

A lot of people think, when you say city planning, that you work at a counter. Because Los Angeles is such a big city, we plan differently than most jurisdictions. There is the counter, project planning, and policy planning. Project planning is more similar to the kind of work done at a counter (where you would get a permit to do a residential project), but the projects are larger, discretionary, and require findings. Policy planning (where we do community planning) defines long-range policies and goals for communities. In Los Angeles, community planning also establishes land use plans and zoning.

What are the goals of the community plans you’ve worked on? What is your mission in working on those projects?

Overall, community planning is aimed toward sustainable communities. In Los Angeles, one of our biggest issues is housing—so creating equitable, affordable housing and increasing density—in a way that will work, which necessitates planning around transit.

In general, as a community planner, you have to think very carefully about where you’re putting things and how they connect to each other. I currently work on the Venice Local Coastal Program, so another significant consideration is how we transition and adapt to sea-level rise.

Are a lot of planners working in the city of Los Angeles, or elsewhere in the city or the country, becoming more focused on sustainability and a holistic picture of sustainability?

It depends on the location. Sustainability as defined by climate change is determined by different factors in different places. For example, in coastal communities, it’s defined by sea-level rise, but in other communities it might be defined by flooding, weather, or fire. Because of recent catastrophic events In California, planning has changed to focus more on resilience.

You’ve been a professional planner since 2013, and you used to be more of a transportation planner, right?

I used to work for the Los Angeles Department of Transportation. I did active transportation planning and implementation. That was very different because it was based in current planning and implementation, versus long-range planning.

What lessons did you take in shifting from transportation as your focus to a long-range policy planning position?

Working in transportation, I came to understand how networks and the connectivity of land uses are integral to planning. Because planning focuses on private property, it doesn’t really comprehend the implications of circulation—even though every plan has a circulation plan—because planners have never worked in the area of circulation. They work in parcels.

City crews installing a bicycle corral and bicycle repair station on Main and 5th streets in Downtown L.A. (Image by Elizabeth Gallardo)

I also went to school for landscape architecture for a year. In that discipline, you focus a lot on user experience and how spaces are built to facilitate behavior. A lot of planning efforts try to effect change, but they don’t consider that you can’t force behavior.

How was it that you came to teach students in planning? What advice could you give you student planners who would also like to teach planning or teach planning to supplement their career?

I fell into teaching. I was asked by the chair of Cal Poly Pomona (who was also my mentor in grad school) to come and teach as soon as I graduated. He just thought I would be good at it. I’ve taught about 12 different classes in my six years of teaching. They’ve all had very different structures—some design-based labs, some lectures, some project-based, some topical seminars.

If you wanted to teach planning as your primary career, you really need to have the terminal degree: a PhD. I considered getting a PhD, but when I considered not working for another three to six years, I decided it was not for me. To really teach well in planning, I think you have to be practicing planning, too. You can’t teach all of planning in theory. That’s just not how planning works. I would say it’s a profession where you would learn most by doing. The model of planning education is flawed because it is largely taught by PhDs who haven’t practiced.

How do you recommend that students negotiate that line between theory and practice?

Most students come to planning because they have a certain set of ideals, vision, and dreams for urban places. That’s a great reason to come into the field. I think that working in the field, you will recalibrate those dreams significantly.

An outreach event for Active Streets L.A., featuring community walk-abouts, education, and mapping for improvements on Budlong Avenue in South L.A. (Image by Elizabeth Gallardo)

You can have a very rewarding career in practice with theory. The most important thing is to continue learning and continue talking about planning, which is pretty well facilitated by the American Planning Association and a variety of speaking and educational enrichment opportunities. Because planning is such a current practice, things are always changing, so you’ll always need to read and learn more and come up with new ideas to solve new problems.

Given the quickly evolving nature of the field, what are some of the lessons you remember specifically from graduate school? What are some of the lessons you still carry with you in your day-to-day practice?

I remember a policy analysis assignment that looked at different solutions to the same problem, weighing costs, benefits, and political buy-in. That was a very realistic approach to planning that prepared me for professional situations I would experience. Policies often change for reasons that aren’t related to making the best policies. There are a lot of politics and other factors like funding and reprioritization. In my career, I saw the rise and fall of active transportation as a fashionable idea, obliterated by self-driving cars.

What are your goals for the rest of your career?

There are two paths I could consider. One path is to stay forever with the city of Los Angeles, which is a very desirable path. In the city of Los Angeles, and in the Department of City Planning, there’s a lot of mobility in where you can go and what you can do, which is pretty amazing. I could realistically say that in 25 years, I might be completely happy here. I don’t think most people could say that about where they work.

Another path would be to go into a more political, policy type environment, which I’m not fully sold on. There is a lot to be said for stability. I’m a single parent, so stability is really important to me.

Does being a parent influence your relationship to your job?

It reveals a lot about how gendered our environment is. In general, I think a lot about how inconvenient it is for people who have to take children places—the reality of getting your child from home to school and back again. I love Starbucks now because they have drive-thrus. The idea of taking my two year old out of his car seat to stand in line for ten minutes at the coffee place is absurd. My theoretical planning brain, however, hates drive-thrus and what they do to neighborhoods.

Being a parent brings to light a lot of issues that are the big-fish complicated issues in planning. Living in a single-family neighborhood is wonderful for children. It’s very clean and safe and pleasant versus living in a multi-family neighborhood. I’ve had both of these experiences recently, I understand a little more the reasons that people are so impassioned over these planning issues.

For a student who’s considering entering the field of planning, or just embarking on graduate studies of planning, what advice would you offer for getting the most out of their education experience?

I suggest nurturing all of your pet curiosities in planning and doing internships as much as possible while in school. Internships are kind of like putting your education on steroids.

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.