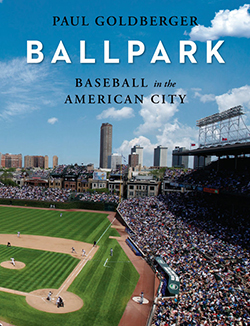

Architecture critic Paul Goldberger analyzes the evolution of baseball stadiums and celebrates their essential connection to cities in "Ballpark: Baseball in the American City."

About midway through Ballpark: Baseball in the American City, Paul Goldberger reports that Dodger Stadium has by now hosted more seasons of baseball than Ebbets Field did.

Pound that into your mitt for a moment.

The juncture is more than just trivial. Ebbets Field was as beloved as American structures get, knitted into the fabric of Brooklyn and into the sinews of American memory. Its cross-country successor belongs to the nation's great 20th century upstart and expressed functional modernism as well as any civic project before or since. The irony of this historic leapfrogging is that, six decades after baseball left Brooklyn, Ebbets is the fresh model for stadium design. Brooklyn is an ascendant American city once again, and Dodger Stadium, while still exceedingly pleasant on a pinkish summer evening, seems of another age—well-meaning and thrilling in its day, but more dated than timeless.

The juncture is more than just trivial. Ebbets Field was as beloved as American structures get, knitted into the fabric of Brooklyn and into the sinews of American memory. Its cross-country successor belongs to the nation's great 20th century upstart and expressed functional modernism as well as any civic project before or since. The irony of this historic leapfrogging is that, six decades after baseball left Brooklyn, Ebbets is the fresh model for stadium design. Brooklyn is an ascendant American city once again, and Dodger Stadium, while still exceedingly pleasant on a pinkish summer evening, seems of another age—well-meaning and thrilling in its day, but more dated than timeless.

This is one of many details—about buildings and about America—that Goldberger reveals in his entertaining, insightful account of the places that house the national pastime. The architecture critic for The New Yorker, Goldberger carries an air of highbrow arrogance that is almost required for major critics. And yet, he loves his Yankees and he unleashes his appreciation for the sporting vernacular and urban vernacular in this excellent book. It is one of the most engaging books to be written on either cities or baseball in the past decade.

The professional game was popularized in Brooklyn, a city urban enough to need pastoral refuge but undeveloped enough to afford space for multiple teams and stadiums in the late 1800s.

Goldberger describes Brooklyn's ramshackle (and flammable) wooden stadiums lovingly. He moves to the early generation of designed stadiums and then to the era of the great steel and concrete stadiums, many of which, despite their size and jubilance, fit harmoniously into urban surroundings. We know their vestiges in the form of Wrigley Field and Fenway Park — both of which Goldberger reveres—and lost gems like Forbes Field (Pittsburgh) and Sportsman's Park (St. Louis).

Goldberger's admiration is emotional, not necessarily aesthetic. Early stadiums were not so much designed as assembled. He writes:

Most of the best ballparks have not, in fact, been particularly memorable pieces of architecture by any formal standard: there're irregular, opportunistic structures, often altered and adjusted over the years to respond to changing market demand and change in urban conditions….even those classic ballparks are better remembered for the world they made within, they're magnificent juxtapositions of soft green playing fields and tough, lyrical steel and concrete structures.

His love for old stadiums jabs at almost all modern and contemporary design principles and certainly at the starchitecture movement of the past two decades. For Goldberger, an expanse of grass, some uneven grandstands, and a view of the city beyond the outfield are what make a ballpark great. Fans attend in part to enjoy the open space and to commune with each other, reveling in a concept that Goldberger refers to as rus in urbe, "a way in which city folk might briefly break away from the grit and noise and pressures of the harsh city and indulge in the delight of rusticity." He loves the old stadiums that appeared to be ordinary buildings from the street but that, once inside, revealed the playing field, almost as if by surprise.

Baseball's slow, clockless pace and abundance of games (162 per team per season) make attending more like a visit to a park—Goldberger notes that only baseball stadiums go by that name (or field)—rather than an event. Baseball is neither an attraction nor an amenity. For Goldberger, it is an essential part of city life.

Goldberger does not set out to catalog every Major League stadium; rather, he chooses a few dozen of those he considers most interesting and historic. Goldberger naturally discusses the development of the original Yankee Stadium, the first self-consciously lavish ballpark, "a building whose designers wanted it to be respected more than liked" (replaced in 2009 with a marble-clad structure of "almost comical self-importance"). He recounts the battles to choose a site and the Yankees' indignity of playing in the Giants' Polo Grounds. Yankee Stadium was followed less successfully by Cleveland's behemoth Municipal Stadium and Baltimore's Memorial Stadium. At every turn, he vividly invokes bygone times and unique places.

The emotional resonance of Ballpark is a testament to Goldberger's thoughtfulness, his love for cities, and the inherently nostalgic quality of America's favorite pastime. His feelings become less tender in the second half of the 20th century.

Following World War II, baseball met the urban fringe first in Milwaukee and then in San Francisco. Anaheim and Kansas City followed. Los Angeles managed a paradox: a site barely a mile from downtown that accommodated acres of parking and afforded not even a glimpse of the urban skyline. All four were built bigger than most of their predecessors, set apart from urban neighborhoods and surrounded by parking lots. They are not nearly as pleasing as are the views of rowhouses and elevated trains rumbling past outfield bleachers.

In short, baseball did what many Americans were doing: move to the suburbs and wed themselves to cars. (Football, Goldberger argues, has no such cozy relationship with cities. Why not? Tailgating is inherent to football, and tailgating requires parking lots.)

Modern design principles took over. New stadiums became symmetrical, abandoning the irregular walls that delight Goldberger and were usually the result of stadiums' close quarters (e.g., Fenway's Green Monster) and emerging fully formed rather than cobbled together (e.g., Tiger Stadium). Many stadium architecture firms were mainly engineering firms. Starting in 1910, one company—Cleveland-based Osborn Engineering—dominated stadium design, including classic stadiums like Shibe Park, Forbes Field, and Ebbets Field. The firm's "work was solid, functional, and generally handsome, if understated." It got less handsome as time went on.

While the modern era produced handsome structures like Dodger Stadium and Kaufman (née Royals) Stadium, it spun out of control. Alongside disastrous urban renewal projects, highways, and unrepentant sprawl, cities tore down venerable, idiosyncratic parks in favor of the "concrete doughnut," designed to accommodate both baseball and football—badly, on both counts. They were arguably pragmatic, for accommodating two sports at once, but it was a pragmatism that ignored all other virtues. He notes that doughnuts were typically publicly funded, thus ushering in the tradition by which private owners exploit the public dollar.

Osborn designed, or set the tone for New York's Shea Stadium, Minneapolis's Metropolitan Stadium, and the true doughnuts such as Pittsburgh's Three Rivers Stadium and St. Louis's Busch Stadium. Philadelphia's Veterans Stadium had "all the charm of a highway underpass." This aesthetic carnage was not just ugly—it was also tedious: "The aspect of the legacy of old ballparks that the postwar years really destroyed was not elegance, of which there was precious little to start, with but idiosyncrasy they all looked, and felt, the same." This trend continued right up to the 1991 opening of the new Comiskey Park (now called Guaranteed Rate Field) in Chicago, which Goldberger describes as "the last of the twentieth century's concrete behemoths."

Then came Camden Yards.

Baltimore's new stadium—now, amazingly, in its 27th season—commands an entire chapter in Ballpark, and rightfully so. It fit into a tight urban lot, near downtown, bounded by real city streets, and rich in architectural detail. From the first moment, fans discovered just what the Modernist era had stolen from them.

Interestingly, Goldberger reveals that the original design for Camden Yards held no such promise. He explains that vaunted HOK was essentially dragged along by enlightened Orioles executives who had far greater appreciation for the site than the firm's architects did. Team management "spoke Jane Jacobs's language at a time when almost no one else in baseball would've known who she was, or cared anything about her ideas." And yet, HOK got the credit—and, through its successor Populous, almost all the subsequent commissions (19 of MLB's 30 extant stadiums, some in partnership with other firms). Of all the retro stadiums designed by HOK, with prominence described by Goldberger as "hegemony" (some in partnership with other firms), Goldberger doesn't declare any of them to be home runs, but he approves of many, from San Diego and San Francisco to Cleveland and Pittsburgh.

He is less approving, though, of parks with roofs. He decries the original wave of domed stadiums—led by Houston's ultra-suburban Astrodome—and is only moderately more sympathetic to 21st century retractable-roof stadiums, with clumsily separate fans from the great outdoors. He's amused by Miami's new ultra-modern stadium, which he equates with a "a huge marshmallow, big and gentle and porous" but describes Milwaukee's Miller Park as "19th-century train shed on top of a 19th-century train station."

While Goldberger celebrates the nuances of many of the major stadiums of the past century, he declines to place them in their broader stylistic or urbanist contexts. He dismisses doughnuts as ugly but he could have gone further to criticize their clumsy expression of brutalism, their brutal relationship with urban renewal, and ham-handed realization of modernist ideals like efficiency. It's as if Goldberger, for all his erudition, did not want to alienate readers who came just for the baseball.

Even more surprising, Goldberger mentions none of the progressive design and planning movements of the past 30 years that arose concurrently with "retro-style" Camden Yards and its successors. The Congress for the New Urbanism was founded in 1993, and the principles of smart growth were germinating at the same time that the Orioles' management was teaching Urbanism 101 to the folks at HOK. Even if these movements do not deserve credit for Camden Yards, Goldberger could at least have noted the parallel swings in style and attitudes towards urban design.

His historiographic shortcoming is that he doesn't report on how regular folk—the fans—felt about stadiums. Did 1920s Bostonians love Fenway Park as much as we do today? Did disco-era Cincinnatians hate Riverfront Stadium as much as we assume they did? Goldberger doesn't say.

For all the success of the new generation of urban ballparks—none perfect, but many pleasant—Ballpark ends ominously.

Baseball charms Goldberger in part because of its infinite reach, beyond the imaginary fence and into the limitless expanse of America. But how do we feel when baseball itself crosses the street and attempts to force the city to do its bidding?

For the past two decades, cities have taken advantage of the new urban ballparks (which they often paid for) by redeveloping surrounding areas to capitalize on the increased vibrancy and spending. This is a subject that Goldberger doesn't discuss in enough depth in the first place but could easily occupy a book of its own. He does comment on teams' attempts to capture that spinoff activity by influencing and even creating surrounding neighborhoods.

In 2017, the Atlanta Braves opened the first new suburban stadium in decades, in the edge city of Cumberland. Rather than surround Sun Trust Park with parking lots, the Braves are co-developing an ersatz "district" called The Battery. The Texas Rangers are tearing down their suburban Globe Life Park, building a new one next door, and developing a similar "entertainment district."

Most ironically, the Cubs have leapt over Clark Street and are developing projects in Wrigleyville—a pleasant, organic urban neighborhood if ever there was one—that have nothing to do with baseball, but everything to do with making a few extra bucks off of their brand and fans. The Cubs have developed a hotel and purchased the apartment buildings that overlook Wrigley. The team charges now admission to sit on the rooftops and peer into the friendly confines. As he fears baseball's creep into the public realm, Goldberger reminds us that "real cities are all different from one another, at least somewhat; they offer us that elusive, difficult to define quality we might describe as a sense of authenticity."

Stadiums and teams, arbitrary though they may be, are what make American cities unique. We don't have cathedrals, castles, and ancient monuments. But we have pennants, trophies, and memories of peaceful battles. In a few cities—two, to be exact—the old battlefields still stand, witnessing ever new generations. If Goldberger has his way, they'll stand forever. Everywhere else, the evolution of America's pastime continues. As does that of its cities.

Ballpark: Baseball in the American City

By Paul Goldberger

Penguin Random House

May 14, 2019

384 Pages

$35

‘Forward Together’ Bus System Redesign Rolling Out in Portland

Portland is redesigning its bus system to respond to the changing patterns of the post-pandemic world—with twin goals of increasing ridership and improving equity.

Plan to Potentially Remove Downtown Milwaukee’s Interstate Faces Public Scrutiny

The public is weighing in on a suite of options for repairing, replacing, or removing Interstate 794 in downtown Milwaukee.

Can New York City Go Green Without Renewable Rikers?

New York City’s bold proposal to close the jail on Rikers Island and replace it with green infrastructure is in jeopardy. Will this compromise the city’s ambitious climate goals?

700-Acre Master-Planned Community Planned in Utah

A massive development plan is taking shape for lakefront property in Vineyard, Utah—on the site of a former U.S. Steel Geneva Works facility.

More Cities Ponder the End of Drive-Thrus

Drive-thru fast food restaurants might be a staple of American life, but several U.S. cities are actively considering prohibiting the development of new drive-thrus for the benefit of traffic safety, air quality, and congestion.

Air Pollution World’s Worst Public Health Threat, Report Says

Air pollution is more likely to take years life off the lifespan of the average human than any other external factor, according to a recent report out of the University of Chicago.

Placer County

City of Morganton

HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research

Dongguan Binhaiwan Bay Area Management Committee

City of Waukesha, WI

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Indiana Borough

Write for Planetizen

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.